Silence (25) - Mai Văn Phấn. Explication par Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya. Traduction française Dominique de Miscault

Explication par Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Traduction française Dominique de Miscault

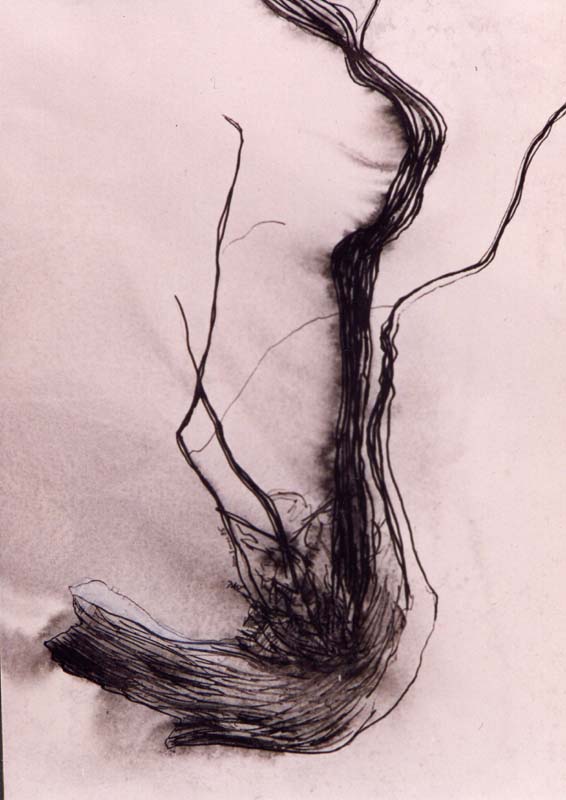

Sự run rảy của cuộc sống - Dominique de Miscault

Silence

25.

Un à un

tombent les pétales

Fragrance

légère et pure

Je ferme la porte

personne n’entrera

Ni le soleil

ni le vent

Bouddha ici

fugitif

entre le récipient et le sol.

Explication du Dr Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Le poète contemple une fleur qui perd ses pétales. La fleur est l'organe reproducteur d'une plante. Il s'agit, ici du cycle de la naissance à la mort et de la renaissance. Pourquoi une renaissance ? La réponse est simple. Nos innombrables désirs nous poussent d'une vie à une autre, affrontant les douleurs de la naissance et de la mort. Un être humain est semblable à une fleur avec ses pétales de désir qui se répandent sur le sol, les uns après les autres. L'être floral du poète. Tandis qu’un parfum léger et pure flotte dans l'air. Trop léger pour arracher le poète à la vie et à son cycle. Quand on est un Bouddha ou un bodhisattva, les peurs et les désarrois du monde ne sont pas oubliés. Le souvenir des souffrances de l'existence ne fait qu'éclairer le chemin d'un bodhisattva vers l'illumination. Lord Siddhârta Buddha pendant la nuit de son illumination a revu les innombrables souvenirs de sa vie passée, dans un flash. Le seul désir des bodhisattvas est de se débarrasser du malheur qui brille dans les gémissements de la vie. Avalokitésvara aurait abandonné ses désirs de libération ou du nirvana jusqu'à ce que sa dernière particule d'existence soit libérée. Il s'est attardé dans l'existence et refusa l'étreinte du nirvana. Aux yeux d'un Bouddha ou d'un bodhisattva, ni le monde ni le nirvana ne sont odieux. Ils regardent les deux avec une équanimité d'esprit. Ainsi, le parfum du désir n'a rien de négatif pour le poète. Il est pur. Avec le parfum d'une fleur qui a déjà perdu ses pétales, le poète ferme sa porte et ne laisse plus personne entrer. Même la lumière du soleil et le vent n’entrent plus. Le poète est en transe : Ses sens ont éteint le monde des regards et des sons, son souffle est suspendu, son esprit est au repos. Dans ce vide, l'image du Seigneur Bouddha apparaît. Où apparait-il ? Dans un espace éphémère. Généralement, nous percevons un temps éphémère dans un espace. C'est notre perception normale. Mais avec le rapide passage du temps, l'espace change également avec la même rapidité. Le souvenir des premières naissances et décès parle aussi d'un espace fugace. Ni le temps ni l'espace ne sont matériels ni éternels. Et voici un poème qui parle d'antiformes. Les points multifonctionnels visuellement interdépendants dans un espace, qui pourraient être utilisés dans différentes combinaisons ou syntaxes, prouvant que l'espace est fluide. Nous sommes conscients des possibilités de différentes significations du même espace à n'importe quel point quantique de l’espace ou du temps. Et dans cet espace fugace, le Bouddha apparaît, c’est l’illumination. Le Bouddha n'appartient ni au monde de l'esprit ni à un monde sans esprit. Le Bouddha est là entre le récipient et le sol. Parce qu’il n’est ni esprit ni non-esprit. Encore une fois, il n'y a pas de monde sans, ni absence du monde. L'illumination n'est ni dans le récipient, ni sur le sol.

Un grand poème qui ouvre sur de nouvelles vues de la perception !

*

L'ouïe, le toucher, l'odorat, la vue et le goût peuvent être comparés à la corolle protégeant le cœur de la fleur, le corps des poètes. Le poète méditant domine ses sens les uns après les autres. Un à un les pétales tombent dessinant des insectes. Les sens dessinent un monde de couleurs, formes et de sons. Le poète observe comment chacun de ses sens parviennent à l’inaction. Mais un parfum imprègne toujours l'air. Un poète ne peut pas s’extraire des couleurs, des formes et des sons. Le poète en méditation est conscient de la beauté du monde. La méditation inactive ses sens, il n'est plus dans le monde des sens. Le poète ferme la porte. Le corps est comparé à une maison avec neuf portes : deux yeux, deux oreilles, deux narines, la bouche, l’anus et l’urètre. En médiation, toutes les portes du corps du poète sont fermées. L'air est éteint. Le poète ne respire plus, plus un souffle de vent. Aucune lumière ne touche la rétine. Ainsi, le monde phénoménal est éteint. L'œil intérieur s'ouvre et les sens regardent vers l'intérieur. Buddha est là. Buddha est en nous. Bouddha est sans nous. L'esprit de Bouddha est omniprésent. Où le poète retrouve-t-il son seigneur ? Ni à l'intérieur ni à l'extérieur. Ni à l'intérieur ni à l'extérieur du poète, ni à l'intérieur ni à l'extérieur du monde. Il n'est ni dans le récipient ni sur le sol. Bouddha n'est plus perçu par les sens, les sens ne le perçoivent pas. Une expérience extraordinaire.

La poésie de Mai Văn Phấn pousse les lecteurs à expérimenter la réalité extra-sensorielle qui n'est ni de notre vie ni de ce monde. On ne trouve nulle part ailleurs ce type de poésie.

Silence (25) by Mai Văn Phấn

Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Translated into French by Dominique de Miscault

Translated into Vietnamese by Takya Đỗ

Long Bien ou le pont de tous les songes - Dominique de Miscault

Silence

25.

One by one

A flower’s petals fall

Fragrance

Is light and pure

I shut the door tight

Not letting anyone in

Nor slanting sunlight

Nor blowing wind

Where Buddha has just appeared

Within the fleeting space

Between the receptacle and the ground.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

Explication

The poet finds a flower shedding its petals. A flower is the reproductive organ of a plant. Hence it stands for birth death and rebirth cycle. Why does rebirth in the maze of worldly life occur? The answer is simple. Our multitudinous desires goad us from one life to another, each life undergoing the pangs of birth and death. A person is like a flower with countless petals of desire. The poet finds the petals of desire shedding one after another from the floral being of the poet. The fragrance however lingers in the air. It is light and pure. No, it is not heavy enough to drag the poet to life and death and rebirth cycle and to the maze of the mundane world. But when one is a Buddha or a bodhisattva he/she does not forget the fret and fever of the world. The memory of the groans of the mundane existence only light the way of a bodhisattva to enlightenment. Lord Siddhartha Buddha during the very night of enlightenment revisited the countless lifestories of his past in the flash of a vision. The only object of the bodhisattvas is to rid the sorrow mickle of the masses weltering in the groans of life. Avalokitesvara is said to have given up the glories of liberation or nirvana. Until and unless the last particle of the existence is liberated he will linger in the existence and refuse the embrace of nirvana. In the eyes of a Buddha or a bodhisattva neither the world nor nirvana is hateful. They look upon both with an equanimity of the mind.So the fragrance of worldly desire has nothing hateful with the poet. It is pure. In the fragrance of a flower that has already shed its petals the poet shuts his door tight not letting any one in. Even sunlight and wind are shut out. The poet is as it were in a trance. His senses have shut out the world of sights and sounds. His breath is suspended. His mind is thoughtless. In this void the image of the Lord Buddha appears. Where does it appear? In the fleeting space. Commonly we see time fleeting in the receptacle of space. That is our mundane perception. But with the fast flow of time the space also changes with equal fastness. The remembrance of earlier births and deaths speak of fleeting space as well. Neither time nor space is a substance Nor is it perennial. And here is a poem that speaks of antiform. The visually interrelated multifunctional points in a space, which could be used in different combinations or syntaxes could prove that space is fluid and we are aware of the possibilities of different meanings of the same space at any point quantum and time quantum. And in this fleeting space Buddha appears, enlightenment appears. The Buddha neither belongs to the world of mind nor does it belong to the world without. The Buddha shines between the receptacle and the ground. Because neither there is mind nor there is no-mind. Again neither there is the world without, nor there is the absence of the world without. So to repeat, enlightenment is neither in the receptacle, nor on the ground, neither not in the receptacle nor not on the ground.

A great poem indeed that opens emergent vistas of perception!

*

Vision, hearing, tactile sense, sense of smell and sense of

taste could be likened to petals around the centre of a flower – that is the

poets body. The poet meditates and he overcomes the senses one after another.

One after another petal falls. The petals draw insects to the flower. The

senses draw to itself the external world of sights and sounds. The poet

observes how one after another sense becomes inactive. But the fragrance

lingers in the air. A poet cannot deny the world of sights and sounds. The poet

in the meditating state is aware of the beauty of the world of senses. But

since meditation has made the senses inactive he is no longer involved in the

world of senses. The poet shuts the door tight. The body could be likened to a

house with nine doors in the two eyes two ears two nostrils mouth anal passage

and urinary passage. And while meditating, all the doors of the poet’s body are

shut. The air is shut out. The poet does not breathe even. There is no blowing

of the wind. No light touches the retina of the poet. So the phenomenal world

is shut out. And the inner eye opens and the senses look inward. And lo! There

is lord Buddha. Buddha is within us. Buddha is without us. Buddha mind is

everywhere. Where does the poet find the lord? He is neither within, nor

without. He is neither not within nor not without, neither not not within nor

notnot without. He is neither in the receptacle nor on the ground. He is

neither perceived with the senses nor not perceived with senses. An

extraordinary experience.

Mai Văn Phấn’s poetry goads the readers to experience the extrasensory

reality which is neither in the worldly life nor not in the worldly. The like

of his poetry is found nowhere.

Tĩnh lặng (25) của Mai Văn Phấn

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya chú giải

Takya Đỗ dịch sang tiếng Việt

25.

Từng cánh hoa

Rơi xuống

Hương thơm

Nhẹ tinh khôi

Đóng kín cửa phòng

Không cho ai vào

Không cho nắng xiên

Không gió thổi

Nơi Đức Phật vừa hiện

Trong khoảng cách mong manh

Giữa đài hoa và mặt đất.

Chú giải:

Nhà thơ thấy một bông hoa đang rụng rơi từng cánh. Bông hoa là cơ quan sinh sản của mỗi loài cây. Vậy nên nó biểu trưng cho chu trình sinh tử và tái sinh [luân hồi]. Tại sao lại xảy ra sự tái sinh trong cái mê cung của cõi phàm trần? Câu trả lời rất đơn giản. Những sự tham luyến vô độ của ta dồn đuổi ta từ kiếp này sang kiếp khác, mỗi kiếp đều phải trải qua những cơn đau sinh nở và hấp hối. Mỗi con người giống như một bông hoa với vô vàn cánh hoa dục vọng. Nhà thơ thấy từng cánh hoa dục vọng đang rơi rụng khỏi đài hoa bản ngã của nhà thơ. Nhưng mùi hương hoa vẫn vương vấn trong không trung. Mùi hương nhẹ và tinh khôi. Không, mùi hương đó không đủ sức nặng để kéo nhà thơ về cõi luân hồi và về cái mê cung của cõi phàm. Song khi một người thành Phật hoặc Bồ tát người đó ắt chẳng quên những nỗi đau sinh lão bệnh tử của trần thế. Kí ức về tiếng kêu than của cuộc tồn sinh nơi cõi thế chỉ soi sáng đường cho vị bồ tát đến với giác ngộ. Đức Phật Thích ca vào chính đêm giác ngộ đã nhớ lại vô vàn những chuyện từ tiền kiếp của ngài trong một sát na.

Mục đích duy nhất của vị Bồ tát là gột rửa vô vàn những nỗi sầu bi cho nhân loại đang đắm chìm trong tiếng than van vì cuộc đời trần thế. Quán Thế âm Bồ tát được cho là đã từ bỏ thiên đường của sự giải thoát hay còn gọi là cõi niết bàn. Một khi sinh linh cuối cùng còn chưa được giải thoát thì ngài còn nấn ná nơi cõi thế và từ chối niết bàn. Trong mắt một vị Phật hay Bồ tát thì cả trần thế lẫn niết bàn đều không đáng bị ghét bỏ. Các vị quán chiếu cả hai cõi với lòng từ bi hỉ xả như nhau. Thế nên mùi hương của dục vọng phàm trần chẳng có gì là đáng ghét đối với nhà thơ. Nó thanh khiết. Trong mùi hương của bông hoa đã bắt đầu rụng cánh, nhà thơ đóng kín cửa phòng không cho ai vào. Đến cả nắng và gió cũng bị cấm cửa. Có thể nói nhà thơ đang nhập định. Tri giác của ông đã khép kín với cảnh vật và âm thanh trần thế. Hơi thở của ông ngừng lại. Tâm trí ông không mảy gợn một suy nghĩ nào. Trong hư không này hình ảnh Đức Phật hiện lên. Hình ảnh ấy hiện lên ở đâu? Trong khoảng cách mong manh.

Người thường chúng ta thấy thời gian lướt nhanh trong khoảng cách mong manh. Đó là nhận thức của phàm nhân chúng ta. Nhưng với một sát na thì khoảng cách đó cũng biến đổi theo với tốc độ nhanh y như vậy. Hồi ức về những cuộc sinh tử luân hồi cũng là nói về một khoảng cách lướt qua nhanh như vậy. Cả khoảng cách lẫn thời gian đều không có thực. Nó cũng không hồi quy. Và đây là bài thơ nói về phản dạng. Các điểm đa năng tương quan trực quan trong một khoảng không gian, mà có thể được sử dụng trong những tổ hợp hoặc cú pháp khác nhau, có thể chứng minh rằng khoảng không có tính biến thiên và chúng ta nhận thức được rằng có khả năng là cùng một khoảng không gian đó sẽ có những ý nghĩa khác nhau tại bất kỳ lượng tử điểm nào và vào bất kỳ lượng tử thời giannào. Và trong cái khoảng cách mong manh đó Đức Phật hiện lên, giác ngộ xuất hiện. Đức Phật không thuộc về thế giới tâm thức cũng chẳng thuộc về thế giới bên ngoài. Đức Phật tỏa chiếu hào quang ở giữa khoảng đài hoa và mặt đất. Bởi lẽ tâm thức là có mà cũng là không. Lại nữa, thế giới bên ngoài cũng là có mà cũng là không. Theo đó mà lặp lại thì giác ngộ không ở nơi đài hoa, cũng không ở nơi mặt đất, cũng chẳng phải không ở đài hoa hay không ở nơi mặt đất.

Quả thực là một bài thơ tuyệt tác mở ra những viễn cảnh hiển hiện trong tri giác.

*

Thị giác, thính giác, xúc giác, khứu giác và vị giác có thể ví

như những cánh hoa quanh tâm một bông hoa – bông hoa đó chính là thân thể nhà

thơ. Nhà thơ đang thiền và ông vượt qua hết giác quan này đến giác quan khác.

Hoa rơi từng cánh. Những cánh hoa thu hút côn trùng đến bông hoa. Các giác quan

thu hút về mình cả thế giới ngoại cảnh đầy âm thanh và hình ảnh. Nhà thơ quan

sát quá trình từng giác quan rơi vào trạng thái tĩnh. Nhưng hương thơm còn bảng

lảng trong không trung. Một nhà thơ thường không thể khước từ cái thế giới âm

thanh và hình ảnh. Nhà thơ trong trạng thái thiền thấy được cái đẹp của thế

giới giác quan. Song do tham thiền đã khiến các giác quan tĩnh lại nên tâm trí

ông không bị thu hút vào thế giới giác quan nữa. Nhà thơ đóng kín cửa phòng.

Thân thể ông có lẽ giống như một ngôi nhà với chín cánh cửa thông ra hai con

mắt, hai lỗ mũi, hai tai, miệng, hậu môn và lỗ tiểu. Và trong lúc hành thiền,

mọi cánh cửa trong thân thể nhà thơ đóng lại. Không khí bị chặn lại bên ngoài.

Thậm chí nhà thơ ngưng thở. Không gió thổi. Không một ánh sáng nào chạm vào thị

giác của nhà thơ. Thế giới hiện tượng bị chặn lại bên ngoài như thế đó. Và tuệ

nhãn mở ra và các giác quan nhìn sâu vào bên trong. Và kìa! Trong tâm có Phật.

Đức Phật ở bên trong chúng ta. Đức Phật ở bên ngoài chúng ta. Phật tâm ở khắp nơi

nơi. Thế nhà thơ thấy Đức Phật ở đâu? Ngài không ở bên trong cũng không ở bên

ngoài. Ngài chẳng phải không ở bên trong cũng chẳng phải không ở bên ngoài,

không tức thị sắc – sắc tức thị không. Ngài không ở trên đài hoa cũng không ở

trên mặt đất. Không thể thấy được Ngài bằng giác quan cũng chẳng phải không thể

thấy được Ngài bằng giác quan. Một trải nghiệm phi thường.

Thơ của Mai Văn Phấn thúc

giục độc giả trải nghiệm thực tiễn ngoại cảm đó, thực tiễn này không ở cuộc sống

phàm trần cũng chẳng phải là không ở cuộc sống phàm trần. Thơ như của ông chẳng

thể thấy ở nơi nào khác.

Cái Không lượng tử được định nghĩa như trạng thái cơ bản của vạn vật, nó vô hướng, trung hòa, mang năng lượng cực tiểu, trong đó vật chất tức là tất cả các trường lượng tử, bị loại bỏ hết. Do những nhiễu loạn của năng lượng trong Không mà vật chất cùng phản vật chất được nảy sinh ra, để rổi chúng tương tác, phân rã trở về với Không, cứ thế tiếp nối cái vòng sinh hủy” (https://thuvienhoasen.org/a23693/vat-ly-hoc-luong-tu-va-phat-giao). (ND)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (1)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (2)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (3)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (4)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (5)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (6)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (7)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (8)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (9)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (10)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (11)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (12)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (13)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (14)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (15)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (16)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (17)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (18)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (19)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (20)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (21)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (22)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (23)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (24)

Ts. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Address: 6/ 1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.0. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal India Pin code711202. Date of Birth 11 02 1947. Education M.A [ triple] M Phil Ph D Sutrapitaka tirtha plus degree in homeopathy. He remains a retired teacher of B.B. College, Asansol, India. He has published books in different academic fields including religion, sociology, literature, economics, politics and so on. Most of his books have been written in vernacular i.e. Bengali. Was awarded gold medal by the University of Calcutta for studies in modern Bengali drama.

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Địa chỉ: 6/ 1 đường Amrita Lal Nath hòm thư Belur Math Dist Howrah Tây Bengal Ấn Độ mã số 711202. Ngày sinh: 11 02 1947. Thạc sĩ văn chương, thạc sĩ triết học, tiến sĩ triết học [bộ ba] cùng với Bằng y học về phép chữa vi lượng đồng cân. Ông còn là một giảng viên đã nghỉ hưu của Trường đại học B.B, Asansol, Ấn Độ. Ông đã có những cuốn sách được xuất bản về nhiều lĩnh vực học thuật bao gồm tôn giáo, xã hội học, văn học, kinh tế, chính trị v.v. Hầu hết sách của ông đã được viết bằng tiếng bản địa là tiếng Bengal. Ông đã được tặng thưởng huy chương vàng của Trường đại học Calcutta về các nghiên cứu nghệ thuật sân khấu Bengal hiện đại.

Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Poétesse - Artiste Dominique de Miscault

Artiste Plasticienne. Actualités. De plages en pages qui se tournent. C’était hier, de 1967 à 1980, mais aussi avant hier. puis de 1981 à 1992. Et encore de 1992 à 2012 bien au delà des frontières. Aujourd’hui, la plage est blanche sous le bleu du soleil. Ecrire en images, cacher les mots porteurs de souffrance ; on ne raconte pas les pas d’une vie qui commence en 1947. C’est en 1969 que j’ai été invitée à exposer pour la première fois. Depuis j’ai eu l’occasion de « vagabonder » seule ou en groupe en France et dans le monde sûrement près de 300 fois. Les matériaux légers sont mes supports, ceux du voyage et de l’oubli.

www.dominiquedemiscault.fr

www.dominiquedemiscault.com

www.aleksander-lobanov.com

Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Nghệ sĩ nghệ thuật thị giác đương đại. Từ bãi biển đến trang giấy. Là ngày hôm qua, từ 1967 đến 1980, và trước đó, rồi từ 1981 đến 1992. Và nữa từ 1992 đến 2012 trên tất cả các biên giới. Ngày hôm nay là bãi biển trắng dưới bầu trời xanh. Viết bằng hình ảnh, giấu từ ngữ mang nỗi đau, người ta không kể lại những bước đi trong cuộc đời tính từ năm 1947. Vào năm 1969, lần đầu tiên tôi được mời triển lãm tác phẩm. Kể từ đó, tôi có cơ hội một mình "lang bạt" hoặc theo nhóm ở nước Pháp và khắp nơi trên thế giới, chắc chắn gần 300 lần. Những chất liệu nhẹ là nguồn hỗ trợ tôi, những chất liệu của hành trình và quên lãng.

www.dominiquedemiscault.fr

www.dominiquedemiscault.com

www.aleksander-lobanov.com

Tác phẩm của Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault. Racines et rameaux - 1 encre - 1982