Silence (31) by Mai Văn Phấn

Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Translated into French by Dominique de Miscault

Translated into Vietnamese by Takya Đỗ

Tác phẩm của Nhà thơ - Họa sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Silence

31

The sky is like a bow

I am in the middle of it

Wind howls

From the top of my head

Through my soles

I breathe earth’s generous air

Into the deep sea

I stretch the bow

For trees to press against mountainous profiles

To compress dawn into night

Like a pine tree

Clutching earth

Stretches its branches to the sky

My heart aimed at the target

Energy concentrated in my belly

I release the bow

The arrow and I fly parallel to the earth’s surface.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

Explication

The poem opens with a skyscape. The sky looks like a bow. That is, it is clear sky meetimg the horizon. The earth is naturally the bowstring. The poet is in the middle of it. His legs are perhaps planted on the ground. And he might be looked upon as an arrow. Or else the poet is in the middle of the space between the dome of the sky and the earth. His situation is almost like that of an astronaut. It seems that the wind that springs from the ground enters through the soles of the poet’s feet and reaches the head where it howls. Curiously enough since the astronauts have to live in vacuum and since they remain weightless, the fluids rush towards the head. A yogi who meditates on the void could feel that he is weightless and the wind might howl in his head. And the poet breathes the earth’s generous air into the seas. Clearly thus the seas which were calm earlier become restless, the winds howling there at all hours. And the poet pulls the bowstring of the earth and shoots an arrow at the trees so that the trees lean against the mountains. The same arrow also nails the dawn into the depths of the primordial night. Dawn rooted into the primordial darkness stretches its branches to the sky. This is the tree of light and life going heaven ward. Thus there is a fresh creation myth where the yogi of the poet finds himself to be the efficient cause remodeling the raw material of the existence to forge the world as it is. Wherefrom does the poet find the immense energy to remodel the world? He does not take any tool from without to shape the world. He uses the tool from within. While the heart of the poet dictates him what to do, the energy generated from the belly helps him to act. The energy centre in the belly is perhaps Manipura chakra or the solar plexus of the esoteric physiology of the subtle body that lurks behind the physical body. But once the arrow is shot the poet also finds himself flung in the air. The arrow could be the words in the present poem. Once the poet flings the arrow of his words the poet also rushes along with them. The arrow is a part of the poets being just as the words are. So the poet finds himself flying with the arrow parallel to the ground. In short the poet is the shooter and the arrow shot as well. Two arrows have been shot at once. That is great feat of an archer. The two arrows could mean the arrow of self and the arrow of non self. With an Indian reader the poem reminds one of Devi Suktam, the Vedic hymn.

There the sixth verse reads- I bend the bow of Rudra to destroy all the enemies of good…..

The seventh verse reads --… My creativity is within the ocean and the waters. Thereby I am present everywhere in the world. The eighth verse reads----When I create the worlds I function like the air. To any casual reader the two paroles viz the parole of the Vedas and the parole of modern sage poet Mai Văn Phấn are similar.

The arrow shot by our poet could be the kulakundalini or the coiled energy slumbering at the Mulaadhaara chakra excelsioring to sahasraara chakra in the head. Or else the arrow is the arrow of truth shot at ignorance so the latter is shattered and battered.

Explication par Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Traduction française Dominique de Miscault

Tác phẩm của Nhà thơ - Họa sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Silence

31

Au milieu

sous la voute céleste

Le vent hurle

de mon crâne

à mes semelles

Je respire l'air de la terre

jusqu’à la mer profonde

L'arc est tendu

arbres écrasés sur le profil des montagnes

comprime l'aube à la nuit

Un pin

arrimé à la terre

étire ses branches vers le ciel

Je vise la cible

l'énergie concentrée dans mon ventre

Je relâche l'arc

la flèche vole parallèlement à la surface de la terre.

Explication

La voute céleste. Le ciel est clair à l’horizon. La terre peut être considérée comme la corde d’un arc, le poète planté au milieu tel une flèche. Ou encore le poète est au milieu de l'espace entre le dôme du ciel et la terre. Sa situation est celle d’un astronaute. Il semble que le vent venant du sol hurle, le pénètre de la plante de ses pieds au sommet de son crâne. Curieusement, en apesanteur, on a constaté chez les astronautes, que les fluides se portent au cerveau. Un yogi qui médite sur le vide peut aussi ressentir qu'il est en apesanteur et le vent peut hurler dans sa tête. Le poète respire l'air généreux de la terre vers les mers. De toute évidence, la mer calme un peu plus tôt, est agitée, maintenant et le vent hurle. Et le poète tire une flèche de la corde de la terre sur les arbres pour qu’ils s'appuient sur les montagnes. La même flèche cloue l'aube dans les profondeurs de la nuit primordiale. L'aube enracinée dans l'obscurité primordiale étend ses branches vers le ciel. C'est l'arbre de lumière et de vie qui s’élance dans les cieux. Ainsi, il existe un nouveau mythe de création où le yogi se trouve être la cause d’un remodelage de la materia prima de l'existence pour créer le monde tel qu'il est. D’où le poète trouve-t-il l'énergie nécessaire à refaçonner le monde ? Il ne prend aucun outil de l'extérieur. Il n’utilise que sa force intérieure. Alors que le cœur du poète lui dicte ce qu'il faut faire, une énergie provenant de son ventre l'aide à agir. Le centre de l'énergie dans le ventre est peut-être le chakra de Manipura ou le plexus solaire dans la physiologie ésotérique du corps subtil qui se cache derrière le corps physique. Mais une fois que la flèche est partie, le poète se retrouve dans l'atmosphère. La flèche pourrait être les mots de ce poème. Une fois que le poète tire la flèche de ses mots, le poète se précipite avec eux. La flèche fait partie des poètes comme les mots. Ainsi, le poète vole avec la flèche parallèlement au sol. En bref, le poète est le tireur et la flèche aussi. Donc deux flèches ont été tirées, à la fois. Quel exploit pour un archer ! Les deux flèches pourraient signifier la flèche du soi et la flèche du non-moi. Pour un lecteur indien, le poème rappelle Devi Suktam, l'hymne védique.

On lit aux versets 6, 7,8 :

je bande l'arc de Rudra pour détruire tous les ennemis du bien ...

... Ma créativité est dans l'océan et les eaux.

C'est pourquoi je suis présent partout dans le monde.

Lorsque je crée les mondes, je fonctionne comme l'air.

Pour tous les lecteurs, les deux paroles, c'est-à-dire la libération inconditionnelle des Védas et la libération inconditionnelle de notre sage poète moderne Mai Văn Phấn, sont similaires. La flèche tirée par notre poète pourrait être le kula Kundalini ou l'énergie enroulée qui dormait dans le chakra du Muladhara supérieur ou le chakra sahasrara dans la tête. Sinon, la flèche est la flèche de la vérité tirée contre l'ignorance, de sorte que cette dernière est brisée et abattue.

Muladhara Chakra est situé à la base du coccyx. Il est le premier des Chakras humains. Le Muladhara Chakra représente la frontière entre la conscience animale et la conscience humaine. Il est lié à l’inconscient, réceptacle dans lequel sont emmagasinées les actions et les expériences de nos vies antérieures. Ainsi, selon la Loi Karmique, ce Chakra contient le cours de notre destinée future. Ce Chakra est également la base du développement de notre personnalité.

Tĩnh lặng (31) của Mai Văn Phấn

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya bình chú

Takya Đỗ dịch sang tiếng Việt

31

Bầu trời cánh cung

Tôi ở giữa

Gió hú

Từ đỉnh đầu

Xuyên qua bàn chân

Khoan hòa khí đất

Tôi thở sâu lòng biển

Giương cánh cung

Cho cây lá ép vào dáng núi

Nén chặt bình minh vào đêm

Tựa cây tùng

Bám đất

Vươn cành lên bầu trời

Tâm hướng đích

Nén khí xuống đan điền

Buông cung

Tôi và mũi tên bay song song mặt đất.

Bình chú:

Bài thơ mở ra với khung cảnh bầu trời. Bầu trời trông như một cánh cung. Tức là bầu trời thanh lãng tiếp giáp với đường chân trời. Mặt đất đương nhiên là dây cung. Nhà thơ đang ở giữa cảnh này. Chân ông có lẽ bám chặt vào đất. Và có lẽ ông được xem như một mũi tên. Nếu không thì nhà thơ đang ở giữa khoảng không gian giữa vòm trời và mặt đất. Trạng thái của ông gần như giống trạng thái của một nhà du hành vũ trụ. Dường như ngọn gió nổi lên từ lòng đất xuyên qua lòng bàn chân của nhà thơ và lên đến đỉnh đầu nơi nó hú lên. Thật kì lạ là khi những nhà du hành vũ trụ phải sống trong môi trường chân không và họ ở trạng thái phi trọng lượng thì chất lỏng dồn hết lên đầu họ. Một người hành thiền đang quán tưởng tính không có thể cảm thấy mình phi trọng lượng và gió có thể hú trên đỉnh đầu người ấy. Và nhà thơ thở khí đất khoan hòa vào lòng biển. Hiển nhiên là vì thế mà biển khơi trước đó vẫn đang tĩnh lặng bỗng trở nên cồn cào, gió ở đó hú suốt ngày đêm không nghỉ. Và nhà thơ kéo dây cung mặt đất và bắn đi mũi tên vào những thân cây để cây lá ép vào dáng núi. Cũng mũi tên ấy đã ghim chặt bình minh vào thẳm sâu đêm tiền sử. Bình minh bắt rễ vào bóng đêm tiền sử ấy đã vươn cành lên bầu trời. Đó chính là cây ánh sáng và sự sống đang vươn lên trời cao. Và như vậy ở đó có một huyền thoại sáng thế mới nơi con người hành thiền trong nhà thơ thấy mình là động lực thúc đẩy việc tái tạo nguyên liệu của hiện tồn để hình thành nên thế giới như hiện tại.

Từ đâu mà nhà thơ tìm thấy nguồn năng lượng khổng lồ ấy để tái tạo mẫu hình thế giới? Ông không dùng bất kì dụng cụ nào từ bên ngoài để tạo hình thế giới. Ông sử dụng dụng cụ nội tại. Trong lúc tâm của nhà thơ định hướng cho ông việc cần làm, thì luồng khí khởi từ đan điền giúp ông hành động. Điểm tập trung khí lực ở bụng có lẽ là luân xa Manipura mà theo theo sinh lý học bí truyền còn được gọi là Búi mặt trời của thân thể hư huyền ẩn sau thân thể vật chất. Nhưng khi mũi tên đã được bắn đi, nhà thơ cũng thấy mình vút đi trong không trung. Mũi tên ấy có thể là những từ ngữ trong bài thơ này. Một khi nhà thơ phóng ra mũi tên từ ngữ của mình, nhà thơ cũng phóng vụt theo chúng. Mũi tên ấy là một phần trong bản thể của nhà thơ chẳng khác gì những từ ngữ kia. Thế nên nhà thơ thấy mình cùng những mũi tên bay song song mặt đất. Tóm lại, nhà thơ là người bắn cung mà cũng là mũi tên được bắn đi. Hai mũi tên đã được bắn đi cùng một lúc. Đó là tài nghệ cực kì điêu luyện của cung thủ. Hai mũi tên có thể ngụ ý mũi tên bản ngã và mũi tên vô ngã. Với một độc giả Ấn Độ, bài thơ này khiến liên tưởng đến một đoạn trong Devi Suktam, bản tụng ca trong kinh Vệ Đà.

Đoạn thơ thứ sáu viết: Ta kéo cây cung của Rudra để tiêu diệt tất thảy mọi kẻ thù của điều thiện...

Đoạn thứ bảy viết: Năng lực sáng tạo của ta nằm trong lòng đại dương và biển cả. Vì thế ta hiện diện ở mọi nơi mọi cõi. Đoạn thứ tám viết: Khi ta sáng tạo ra các cõi, ta nhanh như làn gió thoảng. Đối với bất kỳ độc giả ngẫu nhiên nào, hai cách diễn đạt này, cách diễn đạt trong kinh Veda và cách diễn đạt của nhà thơ tiên tri hiện đại Mai Văn Phấn, tương đồng với nhau.

Mũi tên mà nhà thơ của chúng ta bắn đi có thể là kulakundalini hay búi năng lượng nằm im tại Luân xa Mulaadhaara đang vươn lên Luân xa Sahasraara trên đỉnh đầu. Nếu chẳng phải vậy thì mũi tên đó là mũi tên chân lý bắn vào vô minh khiến vô minh tan tành tiêu tán.

Nguyên văn ‘solar plexus’, chỉ cụm dây thần kinh ở bụng, Luân xa Manipura tiếng Việt đã được dịch ra là Luân xa Búi mặt trời; theo y học và võ thuật Trung Hoa thì vị trí này được gọi là đan điền như nhà thơ đề cập trong bài thơ. (ND)

Ts. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Address: 6/ 1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.0. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal India Pin code711202. Date of Birth 11 02 1947. Education M.A [ triple] M Phil Ph D Sutrapitaka tirtha plus degree in homeopathy. He remains a retired teacher of B.B. College, Asansol, India. He has published books in different academic fields including religion, sociology, literature, economics, politics and so on. Most of his books have been written in vernacular i.e. Bengali. Was awarded gold medal by the University of Calcutta for studies in modern Bengali drama.

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Địa chỉ: 6/ 1 đường Amrita Lal Nath hòm thư Belur Math Dist Howrah Tây Bengal Ấn Độ mã số 711202. Ngày sinh: 11 02 1947. Thạc sĩ văn chương, thạc sĩ triết học, tiến sĩ triết học [bộ ba] cùng với Bằng y học về phép chữa vi lượng đồng cân. Ông còn là một giảng viên đã nghỉ hưu của Trường đại học B.B, Asansol, Ấn Độ. Ông đã có những cuốn sách được xuất bản về nhiều lĩnh vực học thuật bao gồm tôn giáo, xã hội học, văn học, kinh tế, chính trị v.v. Hầu hết sách của ông đã được viết bằng tiếng bản địa là tiếng Bengal. Ông đã được tặng thưởng huy chương vàng của Trường đại học Calcutta về các nghiên cứu nghệ thuật sân khấu Bengal hiện đại.

Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Poétesse - Artiste Dominique de Miscault

Artiste Plasticienne. Actualités. De plages en pages qui se tournent. C’était hier, de 1967 à 1980, mais aussi avant hier. puis de 1981 à 1992. Et encore de 1992 à 2012 bien au delà des frontières. Aujourd’hui, la plage est blanche sous le bleu du soleil. Ecrire en images, cacher les mots porteurs de souffrance ; on ne raconte pas les pas d’une vie qui commence en 1947. C’est en 1969 que j’ai été invitée à exposer pour la première fois. Depuis j’ai eu l’occasion de « vagabonder » seule ou en groupe en France et dans le monde sûrement près de 300 fois. Les matériaux légers sont mes supports, ceux du voyage et de l’oubli.

www.dominiquedemiscault.fr

www.dominiquedemiscault.com

www.aleksander-lobanov.com

Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault

Nghệ sĩ nghệ thuật thị giác đương đại. Từ bãi biển đến trang giấy. Là ngày hôm qua, từ 1967 đến 1980, và trước đó, rồi từ 1981 đến 1992. Và nữa từ 1992 đến 2012 trên tất cả các biên giới. Ngày hôm nay là bãi biển trắng dưới bầu trời xanh. Viết bằng hình ảnh, giấu từ ngữ mang nỗi đau, người ta không kể lại những bước đi trong cuộc đời tính từ năm 1947. Vào năm 1969, lần đầu tiên tôi được mời triển lãm tác phẩm. Kể từ đó, tôi có cơ hội một mình "lang bạt" hoặc theo nhóm ở nước Pháp và khắp nơi trên thế giới, chắc chắn gần 300 lần. Những chất liệu nhẹ là nguồn hỗ trợ tôi, những chất liệu của hành trình và quên lãng.

www.dominiquedemiscault.fr

www.dominiquedemiscault.com

www.aleksander-lobanov.com

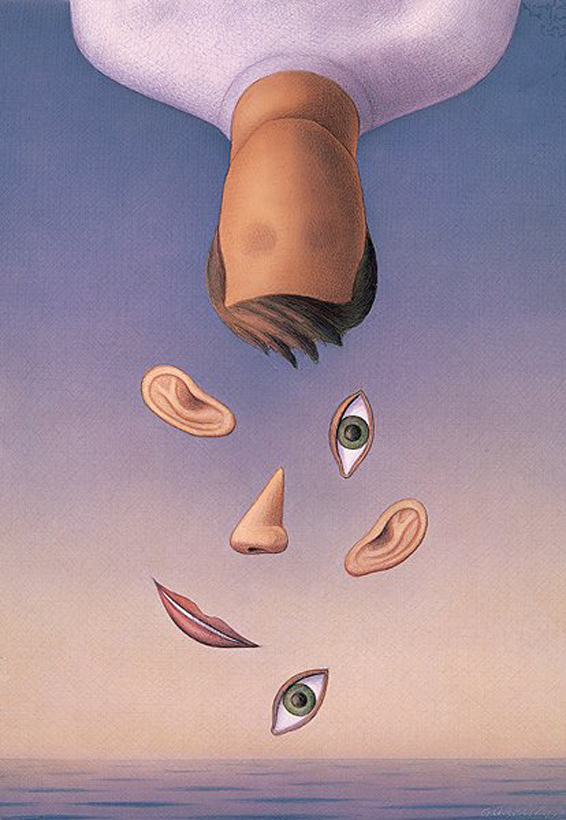

Tác phẩm của HS. Gürbüz Dogan Eksioglu, Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ