Tišina (6). Mai Văn Fấn. U tumačenju Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya. Sa vijetnamskog na engleski jezik preveli: Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard. Sa engleskog na crnogorski jezik prevela Sanja Vučinić & Dusan Djurisic

Mai Văn Fấn - Mai Văn Phấn

U tumačenju Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Sa engleskog na crnogorski jezik prevela Sanja Vučinić & Dusan Djurisic

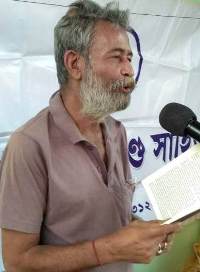

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Nhà thơ Dusan Djurisic

TIŠINA

6.

Crno voće

sazrelo visoko na nebu

gdje lotosi

i hrizanteme cvjetaju

Moja kosa i ramena su bijeli

moja stabljika

počinje da žuti

Crne zone se smanjuju

nestajući brzo

Ruka

zakopava me u jamu

bez vode

Ja

ničem kao mladica u pustinji.

(Sa vijetnamskog na engleski jezik preveli: Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

TUMAČENJE:

Pjesma je ezoterična u suštini i data u nedokučivom i tajanstvenom

slikovitom prikazu koji potresa naš svjesni um. Otvara se crnim voćem sazrelim visoko na nebu, gdJe cvjetaju lotosi

i hrizanteme. Ona mijenja naš pogled na svijet. Zar ne vidimo sunce koje visi

sa neba? Zar ne izgleda kao plod? Dijete Boga vjetra u indijskoj mitologiji

hita da pojede Sunce. Ako se Sunce posmatra kao voćka koja visi sa neba,

očigledno je da je nebo lišće na vrhu drveta koje je izokrenuto. Njegovi

korijeni prodiru u neodređeni kosmički prostor. Njegova stabljika je takođe

tamo u neodređenom kosmičkom prostoru.

Zašto vidimo bijelo Sunce koje visi sa visine? Jer smo

ukorijenjeni u mraku. Kada bi bili na svjetlosti i da smo sami svjetlost, da li

bismo mogli uočiti svjetlost koja visi kao bijeli plod voća? Ne.

Ali pjesnik se već transformisao u svjetlost i on opisuje crno

voće na nebu gdje cvjetaju lotosi i hrizanteme. Nebo je eksternalizacija uma.

Nebo pjesnikovog uma je osvijetljeno hrizantemama – cvijećem poput bijele rade,

sa žutim u sredini. One imaju dekorativne kićanke. Hrizanteme predstavljaju

optimizam i radost. Nebo je takođe osvijetljeno cvjetovima lotosa. Cvjetovi

lotosa izranjaju iz blatnjave zemlje i izbijaju u cvjetanje besprijekorne

čistoće. Oni su simboli sunca. Dakle, možda možemo uzeti slobodu da tvrdimo da

je pjesnik smješten u svijetu koji se razlikuje od našeg. Pjesnik se takoreći

nalazi u antisvijetu gdje je naša zemlja iza neba osvijetljena hrizantemama i

lotosima. Tlo na kome pjesnik sjedi je ono što mi nazivamo nebom sa zemlje. Ali

u viziji pjesnika površina zemlje osvijetljena lotosima i hrizantemama je sva

svjetlost. A u njenom centru se opaža crno voće. Što bi moglo da bude crno

voće? Ukoliko i sam nijesi svjetlost i nijesi na svjetlosti, ne možeš uočiti

crnilo. Ovdje pjesnik očigledno ima postmodernistički doživljaj. Logocentrična

filozofija Zapada govori o svjetlosti kao o središtu. Ali tama je svakako u

središtu svjetlosti. Ili, u suprotnom ne bi moglo biti svjetlosti. Tama ili

crnilo označava tišinu. Kad tišina ne bi postojala u središtu postojanja, ne bi

bilo postojanja uopšte ispunjenog

razlikama i bukom. Čini se da se sam pjesnik pretvara u hrizantemu pri pogledu

na crno voće.

Moja kosa i ramena su bijeli

Moja stabljika

počinje da žuti

Čini se da se crne zone kod pjesnika smanjuju... To jeste, iako je

kao i svaki cvijet ukorijenjen u svjetovnosti zemlje, u samsari, on se

preobražava u cvijet koji je sav sačinjen od ljubavi i svjetlosti. Carstvo cvijeta

se toliko razlikuje od svijeta blata iz kog niče!

Sada kada se pjesnik pretvorio u cvijet on je napustio svijet koji

je ogrezao u samsari i neprekidnoj žalosti. I gle! Neka neodređena ruka ga

zakopava u jamu. Ne treba mu voda. On raste kao mladica u pustinji. On raste

kao mladica u bodhichitta (um prosvjetljenja) ili Buda prirodi. Buda priroda je

lišena svih slučajnih osobina uma i samsare. Ona je nepromjenljiva kao

pustinja. Ona je izvan radosti i tuge, svjetlosti i tame, znanja i neznanja.

Pjesniku, koji je sada cvijet, ne treba sok iz blatnjave zemlje ili samsare

koja je ostavljena s razlikama. On raste kao mladica u beskrajnoj pješčari ili

pustinji. Pustinja je Buda priroda koja nije svjedok bilo kog rođenja ili smrti

i koja je jedna pješčara neprekidne radosti gdje prolazne radosti i tuge

samsare nemaju prostora da se šire. Crno voće u nebesima uma pjesnika je

takođe simbol nirvane i Buda prirode. To je odsustvo svega što doživljavamo u

samsari. To je praznina i vječna tišina koja vrvi od beskrajnih mogućnosti.

Biografija dr Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Adresa: 6/1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.O. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal Indija pin code 711202. Datum rođenja 11 02 1947. Obrazovanje Magistar nauka [trostruki] Magistar filozofije, Doktor nauka Sutrapitaka Tirtha, uz diplomu iz homeopatije. On je i dalje nastavnik u penziji na B.B. College, Asansol, Indija. Do sada je objavio knjige iz različitih akademskih oblasti, uključujući religiju, sociologiju, književnost, ekonomiju, politiku, itd. Većina njegovih knjiga su napisane na narodnom, to jest, bengalskom jeziku. Dobitnik je zlatne medalje Univerziteta u Kalkuti za studije o modernoj bengalskoj drami.

BILJEŠKA O PISCU

Vijetnamski pjesnik Mai Văn Fan je rođen 1955. godine u Ninh Binh, Red River Delta u Sjevernom Vijetnamu. Trenutno, živi i piše poeziju u gradu Hải Phòng. Objavio je 14 knjiga poezije i 1 knjigu "Kritike - Eseji" u Vijetnamu. Njegovih 12 knjiga poezije su objavljene i prodaju se u inostranstvu i na Amazon mreži za distribuciju knjiga. Pjesme Mai Văn Phan-a su prevedene na 23 jezika, uključujući: engleski, francuski, ruski, španski, njemački, švedski, albanski, srpski, makedonski, slovački, rumunski, turski, uzbekistanski, kazahstanski, arapski, kineski, japanski, korejski, indonežanski, tai, nepalski, hindu i bengalski (Indija).

Silence (6) by Mai Văn Phấn

Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Translated into French by Poet Dominique de Miscault

Silence

6.

A black fruit

Ripened high in the sky

Where lotuses

And chrysanthemums are blooming

My hair and shoulders are white

My stalk

Begins to turn yellow

Black areas are shrinking

Vanishing quickly

A hand

Buries me in a pit

Needing no water

I grow as a sapling in the desert.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

Explication:

The poem is esoteric in essence and decked in unfathomable and arcane imagery that jars our conscious mind. It opens with a black fruit ripened high in the sky where lotuses and chrysanthemums are blooming. It changes our world view. Do we not see the Sun hanging from the sky? Does it not look like a fruit? The child of Wind God in Indian mythology rushed to eat the Sun. If the Sun is deemed as a fruit hanging from the sky it is obvious that the sky is the foliage at the top of a tree which is inverted. Its roots go into the indeterminate cosmic space. Its stem is also there in the indeterminate cosmic space.

Why do we see the white Sun hanging from the high.? Because we are rooted in darkness. If we were in the light and if we were light ourselves could we detect the light which hangs like a white fruit? Nope.

But the poet is already transformed into light and he descries the black fruit in the sky where lotuses and chrysenthemums bloom. The sky is the externalization of the mind. The sky of the poets mind is alight with chrysenthemums - the daisy like flowers with yellow at the centre. They have decorative pompons. Chrysenthemums stand for optimism and joy. The sky is also lit with lotus flowers. Lotus flowers spring from the muddy earth and burst into efflorescence of stainless purity. They are sun symbols. So may we take the liberty to argue that the poet is stationed in a world which is different from the world of ours. The poet is as it were in an anti world where the earth of ours is behind the sky lit with chrysenthemums and lotuses. The ground on which the poet is seated is what we call the sky from the earth. But in the poets vision the surface of the earth lit with lotuses and chrysenthemums are all light. And at its centre a black fruit is descried. What could be the black fruit? Unless you are light itself and you are in the light you cannot descry the black. Here the poet is apparently post modern. The logo centric philosophy of the West speaks of light as the centre. But darkness is surely at the centre of light. Or else there could be no light. Darkness or the black stands for silence. If silence were not there at the heart of the existence there could be no existence at all loud with differences and noise. The poet himself seems to turn into chrysanthemum at the sight of the black fruit.

My hair and shoulders are white

My stalk

Begins to turn yellow

The black areas in the poet seem to shrink. That is, though like any flower he is rooted into the earthiness of the earth, into the samsara, he is getting transformed into a flower that is all love and light. The realm of the flower is so different from the world of mud wherefrom it springs!

Now that the poet is transformed into a flower he is removed from the world weltering in samsara and ceaseless sorrow. And lo! Some indeterminate hand buries him in a pit. He needs no water. He grows like a sapling in a desert. He grows like a sapling in the bodhichitta or Buddha nature. Buddha nature is bereft of all the accidental qualities of the mind and samsara. It is as uniform as the desert. It is beyond joys and sorrows, light and darkness, knowledge and ignorance. The poet, a flower now, does not need the sap from the muddy earth or samsara which is lorn with differences. He grows as a sapling in the ceaseless sandscape or the desert. The desert is Buddha nature which doesnot witness any birth or death and which is one sandscape of ceaseless joy where transitory joys and sorrows of the samsara have no room to grow. The black fruit in the minds sky of the poet is also symbolic of nirvana and Buddha nature. It is the absence of all that we experience in the samsara. It is emptiness and perennial silence teeming with infinite possibilities.

Silence (1)

Silence (2)

Silence (3)

Silence (4)

Silence (5)

Tĩnh lặng (6) của Mai Văn Phấn

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya chú giải

Phạm Minh Đăng dịch từ tiếng Anh

Dịch giả Phạm Minh Đăng

Tĩnh lặng

6.

Trái cây màu đen

Chín từ đỉnh trời

Nơi hoa sen

Hoa cúc đang nở

Tóc và vai tôi màu trắng

Chiếc cuống

Bắt đầu ngả vàng

Màu đen đang co lại

Tan nhanh

Có bàn tay

Chôn tôi xuống hố

Không cần nước

Tôi mọc cây non trên sa mạc.

Chú giải:

Bài thơ này trong bản chất là ẩn ngữ và thể hiện ra bằng hình ảnh bí truyền khôn dò gây xao động tâm thức ta. Bài thơ mở đầu với hình ảnh trái chín đen trên trời cao nơi hoa sen và hoa cúc đang nở. Nó thay đổi cái nhìn thế giới của ta. Ta chẳng thấy mặt trời trên bầu trời sao? Nó không giống một trái cây? Đứa con của Thần Gió trong thần thoại Ấn Độ hối hả ăn Mặt Trời. Nếu Mặt Trời như thể trái cây treo trên bầu trời, hiển nhiên rằng bầu trời là vòm lá của một cái cây lộn ngược. Rễ cắm vào không gian vô tận của vũ trụ. Thân cây cũng trong bầu không vô tận đó.

Tại sao ta thấy Mặt Trời trắng treo trên cao? Do ta cắm rễ nơi bóng tối. Nếu ta ở trong ánh sáng và tự chiếu sáng, ta có nhận ra được ánh sáng như một trái trắng không? Không đâu.

Nhưng bởi nhà thơ đã hóa thân thành ánh sáng, ông thấu thị trái cây đen trên bầu trời nơi hoa sen và hoa cúc nở. Bầu trời là sự trải rộng của tâm trí. Bầu trời trong tâm trí nhà thơ sáng lên cùng hoa cúc – loài hoa vàng tại tâm.Hoa mang những hình cầu điểm trang, biểu trưng cho sự lạc quan và niềm vui. Bầu trời còn sáng bởi hoa sen. Hoa sen nở từ bùn đất và bung nổ thành các hạt bụi trong suốt không tì vết. Hoa sen là biểu tượng mặt trời. Và ta có thể lấy sự tự do này để tranh luận rằng nhà thơ đang đứng trên một thế giới khác biệt với thế giới của chúng ta. Nhà thơ ở một thế giới đối ngược, một phản-thế giới, nơi trái đất của chúng ta bên dưới bầu trời sáng lên bởi hoa sen và hoa cúc. Mặt đất nơi nhà thơ ngồi lại ta gọi là bầu trời từ điểm nhìn trái đất. Còn trong nhãn quan của nhà thơ, bề mặt trái đất được chiếu sáng toàn thể bởi hoa sen và hoa cúc. Nơi chính giữa là một trái cây đen được nhìn thấu. Trái cây màu đen này có thể là cái gì? Nếu ta không phải là ánh sáng tự thân và ta ngập trong ánh sáng, ta không thể thấy được màu đen. Ở đây, nhà thơ hiển nhiên hậu hiện đại. Triết lý vị ngã phương Tây nói ánh sáng như là cái trung tâm ấy. Nhưng chắc chắn là, bóng tối lại ở trung tâm của ánh sáng. Hoặc rằng hẳn là không có ánh sáng. Bóng tối hay màu đen chỉ sự tĩnh lặng. Nếu sự tĩnh lặng không ở tâm điểm của Tồn tại, sẽ không có tồn tại nào cất lời với những khác biệt và tiếng ồn. Bản thân nhà thơ như đang chuyển hóa thành hoa cúc trong cái nhìn của trái cây đen.

Tóc và vai tôi màu trắng

Chiếc cuống

Bắt đầu ngả vàng

Các vùng đen trong nhà thơ như đang co rút lại. Quả thế, như mọi bông hoa, nhà thơ cắm rễ nơi tinh chất trần gian của trái đất, trong cõi luân hồi, ông biến chuyển thành bông hoa đầy ắp tình yêu và ánh sáng. Địa hạt của hoa thật khác biệt với thế giới bùn đất nơi chúng mọc lên!

Giờ đây nhà thơ hóa thân thành bông hoa, được nhấc khỏi thế giới hỗn độn trong cõi luân hồi và nỗi buồn bất tận. Và kìa! Những bàn tay vô định chôn ông xuống hố. Ông không cần nước. Ông mọc như cây non trên sa mạc. Ông mọc như cây non trong Phật tính hay bồ - đề - tâm. Phật tính khước bỏ các phẩm tính ngẫu nhiên của tâm trí và luân hồi. Nó nhất thể như sa mạc. Vượt trên cõi vui buồn, ánh sáng và bóng tối, tri thức và mông muội. Nhà thơ, hiện là một bông hoa, không cần dưỡng chất từ bùn đất hay cõi luân hồi bị hoang hoá trong khác biệt. Ông lớn lên như một cây non trên dải cát dài bất tận hay sa mạc. Sa mạc mang Phật tính không chứng cho bất kì sự sinh hay sự chế nào, là phong cảnh cát của niềm vui bất tận nơi niềm vui và nỗi buồn hư huyễn của luân hồi không còn nơi sinh trưởng. Trái cây đen trong bầu trời tâm trí của nhà thơ cũng là biểu trưng của niết bàn và Phật tính. Đó cũng là sự thiếu vắng của tất cả những gì ta trải nghiệm trong luân hồi. Đó là sự trống vắng và im lặng trường kỳ chứa đầy những khả thể vô hạn.

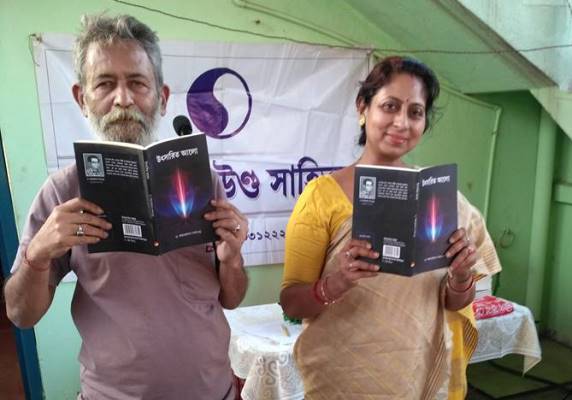

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya và TS. Mousumi Ghosh (Ấn độ)

Explication du Dr Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Traduit de l'anglais par Dominique de Miscault

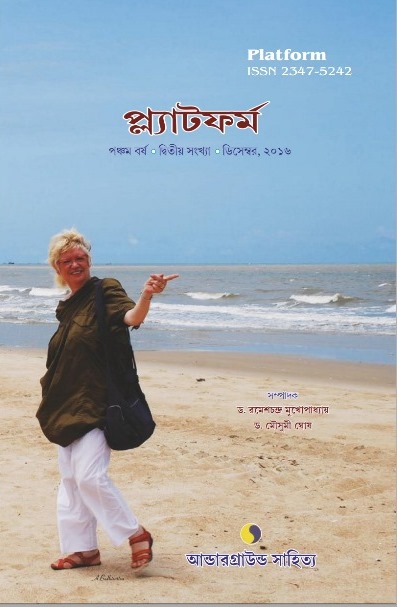

Nhà thơ-Nghệ sỹ Dominique de Miscault trên bìa tạp chí Platform, Ấn Độ, 12/2016

Silence

6.

Un fruit noir

Mûri haut dans le ciel

Où les lotus et les chrysanthèmes fleurissent

Mes cheveux et mes épaules sont blancs

ma tige

tourne au jaune

Les zones noires se rétrécissent

disparaissent rapidement

Une main

m'enterre dans un trou

Ne nécessitant pas d'eau

Je grandis comme un jeune arbre dans le désert

Explication:

Le poème est ésotérique, images insondables et mystérieuses qui remplissent notre esprit conscient. Il s'ouvre avec un fruit noir mûri haut dans le ciel où les lotus et les chrysanthèmes fleurissent. Cela change notre vision du monde. Ne voyons-nous pas le Soleil suspendu au ciel ? L'enfant du Dieu du vent dans la mythologie indienne s'est précipité pour manger le Soleil. Si le Soleil est considéré comme un fruit suspendu au ciel, il est évident que le ciel est le feuillage au sommet d'un arbre qui Est inversé. Ses racines vont dans l'espace cosmique. Sa tige est également là dans l'espace cosmique.

Pourquoi voyons-nous le Soleil blanc suspendu ? Parce que nous sommes enracinés dans les ténèbres. Si nous étions dans la lumière et si nous étions légers nous pourrions détecter la lumière qui pend comme un fruit blanc ? Non.

Mais le poète est déjà lumière et il aperçoit les fruits noirs dans le ciel où fleurissent les lotus et les chrysanthèmes. Le ciel est l'extériorisation de l'esprit. Le ciel de l'esprit des poètes est allumé par les chrysanthèmes - la marguerite comme beaucoup de fleurs avec son cœur jaune. Ils ont des pompons décoratifs. Les chrysanthèmes représentent l'optimisme et la joie. Le ciel est également éclairé par des fleurs de lotus. Les fleurs de lotus jaillissent de la terre boueuse et éclatent en efflorescence de pureté. Ce sont les symboles du soleil. Pouvons-nous donc prendre la liberté de soutenir que le poète serait dans un monde différent du notre. Le poète est comme dans un antimonde où la terre est derrière le ciel, éclairée de chrysanthèmes et de lotus. Le sol sur lequel le poète est assis est ce que nous appelons le ciel de la terre. Mais dans la vision des poètes, la surface de la terre éclairée de lotus et de chrysanthèmes est toute légère. Et au centre, un fruit noir est aperçu. Qu’est ce que ce fruit noir ? Sauf si vous êtes la lumière elle-même et vous êtes dans la lumière, vous ne pouvez pas voir le noir. Ici le poète est apparemment post-moderne. La philosophie centrée sur l'Occident parle de la lumière comme centre. Mais l'obscurité est sûrement au centre de la lumière. Ou bien il n'y aurait pas de lumière. L'obscurité ou le noir représente le silence. Si le silence n'était pas là au cœur de l'existence, il ne pouvait y avoir d'existence à tous les bruits avec toutes les différences de bruit. Le poète lui-même semble se transformer en chrysanthème à la vue du fruit noir.

Mes cheveux et mes épaules deviennent blancs

Ma tige

Commence à virer au jaune

Les zones noires du poète semblent se rétrécir. C'est-à-dire que, comme toute fleur, il est enraciné dans la terreur de la terre, dans le samsara, il se transforme en une fleur qui est tout amour et lumière. Le royaume de la fleur est si différent du monde de la boue d'où il jaillit !

Maintenant que le poète est transformé en fleur, il est élevé au dessus du monde se mêlant au samsara et la douleur incessante. Et voilà ! Une main les enterre dans un trou. Il n'a pas besoin d'eau. Il grandit comme un arbre dans un désert. Il se développe comme un jeune arbre dans la nature bodhichitta ou Bouddha. La nature du bouddha est dépourvue de toutes les qualités accidentelles de l'esprit et du samsara. Il est aussi uniforme que le désert. Il est au-delà des joies et des peines, de la lumière et des ténèbres, de la connaissance et de l'ignorance. Le poète, fleur maintenant, n'a plus besoin de la sève de la terre boueuse ou du samsara qui sont abandonnées aux différences. Il se développe comme un arbre dans un paysage désert sans limite. Le désert est la nature du Bouddha qui n’a besoin d'aucune naissance ou de mort et qui est un désert de joie sans fin où les joies et les peines passagères du samsara n'ont plus de place. Le fruit noir dans le ciel de l’esprit du poète est aussi symbolique du nirvana et de la nature du Bouddha. C'est l'absence de tout ce que nous éprouvons dans le samsara. C'est la vacuité et le silence perpétuel qui grouille de possibilités infinies.

Dominique de Miscault: “Long Biên cây cầu của những giấc mơ”, 2009

Tĩnh lặng (6) của Mai Văn Phấn

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya chú giải

Mai Thái Ngọc Minh dịch từ tiếng Pháp

Mai Thái Ngọc Minh ở Paris 2016

Tĩnh lặng

6.

Trái cây màu đen

Chín từ đỉnh trời

Nơi hoa sen

Hoa cúc đang nở

Tóc và vai tôi màu trắng

Chiếc cuống

Bắt đầu ngả vàng

Màu đen đang co lại

Tan nhanh

Có bàn tay

Chôn tôi xuống hố

Không cần nước

Tôi mọc cây non trên sa mạc.

Chú giải:

Bài thơ bí hiểm, hình ảnh không thể dò thấu và thần bí gây chấn động tâm trí nhận thức của chúng ta. Nó mở đầu bằng một trái cây màu đen chín trên trời, nơi hoa sen và hoa cúc đang nở. Điều này làm thay đổi cách nhìn của chúng ta về thế giới. Chúng ta không nhìn thấy Mặt trời treo trên cao sao? Mặt trời không giống một trái cây sao? Con trai của thần Gió trong truyền thuyết Ấn Độ vội vàng để ăn Mặt trời. Nếu coi Mặt trời là một trái cây treo trên trời, thì hiển nhiên bầu trời là tán lá trên đỉnh của cái cây bị treo ngược. Rễ của nó đi vào không gian vũ trụ vô định. Thân của nó cũng trong không gian vũ trụ vô định.

Tại sao chúng ta nhìn thấy Mặt trời trắng treo trên cao? Bởi vì chúng ta bị chôn rễ trong bóng tối. Nếu chúng ta ở trong ánh sáng và nếu bản thân chúng ta là ánh sáng, liệu chúng ta có thể nhận thấy ánh sáng treo như một trái cây màu trắng? Không.

Nhưng chính nhà thơ đã biến thành ánh sáng và ông nhìn thấy quả màu đen trên bầu trời nơi hoa sen và hoa cúc đang nở. Bầu trời là sự ngoại hiện của tâm trí. Bầu trời tâm trí của các nhà thơ được thắp sáng bởi hoa cúc – loài hoa với tâm màu vàng. Chúng có những bông trang trí. Hoa cúc đại diện cho sự lạc quan và niềm vui. Bầu trời cũng được thắp sáng lên bởi hoa sen. Hoa sen mọc lên từ bùn và nở ra sự thanh khiết. Đó là những biểu tượng của mặt trời. Vậy chúng ta có thể tự do kết luận rằng nhà thơ ở trong một thế giới khác với chúng ta. Nhà thơ như ở trong thế giới đối lập, nơi trái đất của chúng ta ở phía sau bầu trời được thắp sáng bởi hoa cúc và hoa sen. Mặt đất, nơi nhà thơ ngồi, nên chăng gọi là bầu trời từ trái đất. Nhưng trong cách nhìn của các nhà thơ, mặt đất thắp sáng bởi hoa sen và hoa cúc. Và ở tâm, một quả đen xuất hiện. Trái cây màu đen này có thể là gì? Trừ khi bạn là ánh sáng và bạn ở trong ánh sáng, bạn không thể nhìn thấy màu đen. Ở đây, tác giả hẳn thuộc về hậu hiện đại. Triết lý tập trung về phương Đông nói về ánh sáng như trung tâm. Nhưng bóng tối chắc chắn ở trung tâm của ánh sáng. Hoặc là không có ánh sáng. Bóng tối hoặc màu đen đại diện cho sự im lặng. Nếu sự im lặng không nằm ở tâm của sự tồn tại, có thể sẽ không có sự tồn tại của ồn ào trong tất cả sự khác biệt của tiếng động. Bản thân nhà thơ dường như biến thành hoa cúc khi so với trái cây màu đen.

Tóc và vai tôi màu trắng

Chiếc cuống

Bắt đầu ngả vàng

Những vùng đen của nhà thơ dường như thu lại. Có nghĩa là, như mọi loài hoa, cắm rễ xuống đất, trong luân hồi, nó biến thành một bông hoa đầy tình yêu và ánh sáng. Vương quốc của bông hoa thật khác biệt với thế giới bùn lầy nơi nó mọc lên.

Chính bây giờ nhà thơ biến thành hoa rời khỏi thế giới lẫn lộn của luân hồi và nỗi đau không ngừng. Và đây! Một bàn tay chôn chúng xuống hố. Ông không cần nước. Ông lớn lên như một cái cây trong sa mạc. Ông phát triển giống một cây non trong Bồ đề tâm và bản chất của Phật. Bản chất của Phật là lấy đi những phẩm chất ngẫu nhiên của tâm trí và luân hồi. Nó thống nhất như sa mạc. Nó vượt lên niềm vui và nỗi buồn, ánh sáng và bóng tối, kiến thức và sự thiếu hiểu biết. Nhà thơ, giờ là bông hoa, không còn cần nhựa sống từ bùn đất hay luân hồi, nơi bị bỏ rơi với sự khác biệt. Ông phát triển như một cái cây trong sa mạc không giới hạn. Sa mạc là bản chất của Phật, cái không cần bất kỳ sự sản sinh hay cái chết và là một sa mạc với niềm vui bất tận nơi những niềm vui và nỗi buồn nhất thời của luân hồi không có chỗ để phát triển. Trái cây màu đen trong tâm trí của nhà thơ cũng là biểu tượng của niết bàn và bản chất Phật. Đó là sự vắng mặt của tất cả những gì chúng ta trải qua trong luân hồi. Đó là sự trống trải và sự im lặng lưu niên đầy ắp với những khả năng vô hạn.

Tĩnh lặng (1)

Tĩnh lặng (2)

Tĩnh lặng (3)

Tĩnh lặng (4)

Tĩnh lặng (5)

Biography of Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Address: 6/ 1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.0. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal India Pin code711202. Date of Birth 11 02 1947. Education M.A [ triple] M Phil Ph D Sutrapitaka tirtha plus degree in homeopathy. He remains a retired teacher of B.B. College, Asansol, India. He has published books in different academic fields including religion, sociology, literature, economics, politics and so on. Most of his books have been written in vernacular i.e. Bengali. Was awarded gold medal by the University of Calcutta for studies in modern Bengali drama.

Tiểu sử Tiến sĩ Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Địa chỉ : 6/ 1 đường Amrita Lal Nath hòm thư Belur Math Dist Howrah Tây Bengal Ấn Độ mã số 711202. Ngày sinh : 11 02 1947. Thạc sĩ văn chương, thạc sĩ triết học, tiến sĩ triết học [bộ ba] cùng với Bằng y học về phép chữa vi lượng đồng cân. Ông còn là một giảng viên đã nghỉ hưu của Trường đại học B.B, Asansol, Ấn Độ. Ông đã có những cuốn sách được xuất bản về nhiều lĩnh vực học thuật bao gồm tôn giáo, xã hội học, văn học, kinh tế, chính trị v.v. Hầu hết sách của ông đã được viết bằng tiếng bản địa là tiếng Bengal. Ông đã được tặng thưởng huy chương vàng của Trường đại học Calcutta về các nghiên cứu nghệ thuật sân khấu Bengal hiện đại.

Sáng sớm ở Bengal Ấn Độ