Tišina (3). Mai Văn Fấn. U tumačenju Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya. Sa vijetnamskog na engleski jezik preveli: Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard. Sa engleskog na crnogorski jezik prevela Sanja Vučinić & Dusan Djurisic

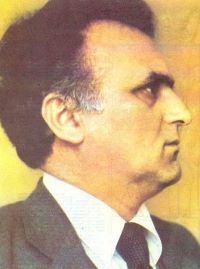

Mai Văn Fấn - Mai Văn Phấn

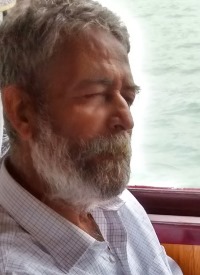

U tumačenju Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Sa engleskog na crnogorski jezik prevela Sanja Vučinić & Dusan Djurisic

Tiến sỹ Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Nhà thơ Dusan Djurisic

TIŠINA

3.

Snop svjetlosti okružuje

mene

u podnožju oltarske kupole

Približava se licu mog oca

(njega nema već tri godine)

Približava se licu moje bake

(nje nema već 27 godina)

Moj otac se oporavio od drhtanja ruku

Moja baka nije više povijena

Svako od njih uči me kako da zapamtim

način da zaboravim

Ja sam providan

Dok odlazim

držeći u ruci

cvijet.

(Sa vijetnamskog na engleski jezik preveli: Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

TUMAČENJE:

U prethodnom dijelu pjesnik je meditirao o potoku života u planini

koji teče postojano u jezero ne praveći buku. I kada pjesnik pogleda u providno

jezero, mlaz svjetlosti okružuje pjesnika. Mlaz podrazumijeva tok. I kada mlaz

svjetlosti okružuje pjesnika to je kinestetski slikoviti prikaz koji se odnosi

na osjećaj tjelesnog kretanja. Drugim riječima, pjesnik smatra da je njegovo

cijelo tijelo, uključujući emocije i čula, kretanje. Tijelo pjesnika se

transformiše u podnožju oltarske kupole. Ranije smo vidjeli potok u trenutku

pada u prozirno jezero bez ikakvog zvuka. Čini se da jezero odražava tok potoka

ili tok života kao podnožje oltarske kupole. Možda smo sišli sa planine i kada

dođemo do smrti mi shvatamo da je podnožje oltara neopisiva uzvišenost i da je

život neprekidna molitva. Kada stignemo do jezera, na dnu postajemo svjesni

oltarske kupole i odjednom život koji je očigledno pun tuge postaje mlaz

svjetlosti koji se sliva sa neopisivog misterioznog beskraja koji se može

razumjeti samo kada spoznamo smrt. I mi počinjemo da obožavamo život koji se

smjestio u podnožju oltara.

Život je oltarska kupola ili Butsudan (Budina kuća) koji nas može

dovesti do neizrecivog. Ovo nas navodi na izazov da se vratimo u vrijeme i

prostor prkoseći zakonima termodinamike. Kada se vratimo u vrijeme i prostor

srećemo našeg oca, baku i majku. Svako od njih nas uči kako da zaboravimo.

Keats (Kits) je nastojao da zaboravi groznicu i uzrujanost života. Prvo je

mislio da bi alkohol mogao da mu pomogne da pobjegne od vapaja postojanja.

Kasnije je mislio da bi mogao da se pridruži slavuju koji nikada nije spoznao u

svom lisnatom svijetu ono što mi ovdje znamo u ovom našem zemaljskom svijetu.

Tako on prati pticu na nevidljivim krilima poezije i nestaje u mračnoj šumi

daleko od sfere tuge. Ali, nakon nekog

vremena usamljena riječ sine mu na pamet i poremeti pjesnikova sanjarenja. Tako

nas ni alkohol ni mašta ne mogu prenijeti iz vapaja postojanja. Čovjek mora da

sagleda život u cjelosti u trenutku smrti i shvati da bi tu moglo da bude

ponovno rađanje. Pun živosti sa svježim dahom života, kada bi mogao ići protiv

vremena i zakona termodinamike, čovjek se susrijeće sa svojim precima. O čemu

god Mai Văn Fấn piše, on piše iz

iskustva. Njegov otac je bolovao od Alchajmerove bolesti i umro. Ali, pjesnik

ga sada sreće u trenutku kada sagledava život staloženo i kao cjelinu. On

zatiče oca bez ikakvog fizičkog oboljenja. Pjesnikov susret sa ocem podsjeća

na Eneja koji se susrijeće sa svojim ocem u Virgil. U stvari, susret sa mrtvim

ocem je motiv koji se ponavlja u herojskoj poeziji. I ovo je takođe fragment

herojske poezije u pravom smislu. Ovdje pjesnik susrijeće svog oca i majku i

djeda. Naše umove i čula uvijek privlači spoljni svijet iluzije. Junak pjesnika

Mai Văn Fấna ih primorava da sagledaju nutrinu našeg bića i da na taj način idu

protiv toka - plime vremena kroz meditaciju. Prema budističkoj kosmologiji

postoji trideset jedna ravan postojanja. Među njima, šest ravni postojanja

pripadaju kamaloka-i (čulnom svijetu). Ljudsko carstvo je samo jedna od njih.

Stoga, naši roditelji su možda napustili ljudsko carstvo. Ali obično oni

itekako postoje u nekom drugom svijetu, možda Kama-loka-i. I pjesnik srijeće

svoje umrle pretke u drugim ravnima kamaloka-e. I gle! Otac ne pati više od

Alchajmerove bolesti, a baka više nije povijena. Kako je to moguće? Teorija

Uslovljenog nastanka pretpostavlja da sve što se dešava u postojanju zavisi od

brojnih uzroka i uslova, a time i sve što se dešava u postojanju nema suštinu.

Stoga, sam prizor umrlih oca i bake oslobođenih fizičkih bolesti uči pjesnika

da ništa u postojanju nema suštinu. Oni uče pjesnika kako se mogu zaboraviti

patnje svijeta. I onog trenutka kada shvatimo da svijet u kome patimo i patnje

koje doživljavamo u svijetu nemaju suštinu i kada spoznamo da su samo zablude,

tek tada ih se možemo osloboditi. Ovo znanje čini pesnika transparentnim

lišenim svireposti svjetovnog postojanja. On se uzdiže iznad Kamaloka-e i uzvikuje.

Dok odlazim

držeći u ruci

cvijet.

Cvijet je lotos. Iako je pjesnik rođen u svijetu i

odrastao u svijetu on više nije uprljan svijetom.

Biografija dr Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Adresa: 6/1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.O. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal Indija pin code 711202. Datum rođenja 11 02 1947. Obrazovanje Magistar nauka [trostruki] Magistar filozofije, Doktor nauka Sutrapitaka Tirtha, uz diplomu iz homeopatije. On je i dalje nastavnik u penziji na B.B. College, Asansol, Indija. Do sada je objavio knjige iz različitih akademskih oblasti, uključujući religiju, sociologiju, književnost, ekonomiju, politiku, itd. Većina njegovih knjiga su napisane na narodnom, to jest, bengalskom jeziku. Dobitnik je zlatne medalje Univerziteta u Kalkuti za studije o modernoj bengalskoj drami.

BILJEŠKA O PISCU

Vijetnamski pjesnik Mai Văn Fan je rođen 1955. godine u Ninh Binh, Red River Delta u Sjevernom Vijetnamu. Trenutno, živi i piše poeziju u gradu Hải Phòng. Objavio je 14 knjiga poezije i 1 knjigu "Kritike - Eseji" u Vijetnamu. Njegovih 12 knjiga poezije su objavljene i prodaju se u inostranstvu i na Amazon mreži za distribuciju knjiga. Pjesme Mai Văn Phan-a su prevedene na 23 jezika, uključujući: engleski, francuski, ruski, španski, njemački, švedski, albanski, srpski, makedonski, slovački, rumunski, turski, uzbekistanski, kazahstanski, arapski, kineski, japanski, korejski, indonežanski, tai, nepalski, hindu i bengalski (Indija).

Silence (3) by Mai Văn Phấn

Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Ts. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Silence

3.

A stream of light is surrounding

Me

At the foot of the altar tower

Drawing near to my father’s face

(He was 3 years gone)

Drawing near to my grandmother’s face

(She was 27 years gone)

My father has recovered from hand trembles

My grandmother no longer stoops

Each of them teaches me how to remember

A way to forget

I am transparent

As I leave

Holding in my hand

A flower.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

Explication:

In the earlier section the poet meditated on the stream of life in the mountain that flows steadily into a lake without making a noise. And when the poet sees into the transparent lake a stream of light surrounds the poet. Stream implies a flow. And when a stream of light surrounds the poet it is a kinaesthetic imagery which pertains to a sense of bodily motion. In other words the poet feels that his whole body including emotions and senses is a movement. The poet’s body is transformed at the foot of the altar tower. Earlier we saw a stream in a moment falling in a transparent lake without any sound. The lake seems to reflect the course of the stream or the flow of life as the foot of altar tower. May be we have come down from the mountain and when we reach death we understand it is the foot of an altar indescribable sublime and life is a continuous prayer. Once we reach the lake at the bottom we become aware of the altar tower and at once the life which is apparently full of sorrow becomes a stream of light flowing down from the indescribable inscrutable infinitude which can be understood only when we see into death. And we begin to worship life seated at the feet of the altar tower. Life is an altar tower or a butsudan that could reach us to the unnameable. This puts in our mind the challenge to go back in time and space defying the laws of thermodynamics. Once we go back in time and space we meet our father grand mother and mother. Each of them teaches us how to forget. Keats sought to forget the fever and fret of life. First he thought of alcohol which might help him to escape from the groans of the existence. Later he felt that he could accompany the nightingale which has never known in its leafy world what we know here in the mundane world of ours. So he follows the bird on the viewless wings of poesy and fades into the dim forest far off from the sphere of sorrow. But after a time the word forlorn flashes upon his mind and it shatters the poets reverie. Thus neither alcohol nor fancy can transport us from the groans of existence. One must see life as a whole at the point of death and learn that a rebirth could be there. Vibrant with a fresh lease of life if one could go against time and the laws of thermodynamics one meets one’s forefathers. Whatever Mai Văn Phấn writes he writes from experience. His father suffered from alzheimers disease and died. But the poet meets him now that he sees life steadily and as a whole. He finds his father sans any physical ailment. The poet meeting his father reminds one of Aeneas meeting his father in Virgil. In fact meeting one’s dead fathers is a recurrent motif in heroic poetry And this is also a fragment of heroic poetry as it were. Here the poet meets his father and mother and grandfather. Our minds and senses are always drawn outward to the world of delusion. The hero of the poet Mai Văn Phấn forces them to look inward and thereby to go against the flow- tide of time through meditation. According to Buddhist cosmology there are thirty one planes of existence. Among them six planes of existence belong to kamaloka.Human realm is only one of them.So our parents may have left the human realm. But ordinarily they very much exist in some other realm, may be of the kama loka. And the poet meets his deceased ancestors in other planes of kamaloka. And lo! father does not suffer from alzheimers disease any longer and the grandmother does not stoop any longer. How come this is possible? The theory of Dependent Origination posits that whatever takes place in the existence is dependent on numerous causes and conditions and hence whatever takes place in the existence has no essence. Therefore the very sight of the deceased persons of father and grandmother free from physical ailments teaches the poet that nothing in existence has any essence. They teach the poet how could they forget the sufferings of the world. Once we know that the world in which we suffer and the sufferings that we experience in the world have no essence and once we know that they are mere delusions we can get rid of them. This knowledge makes the poet transparent bereft of the crudities of worldly existence. He transcends the kamaloka too and exclaims.

As I leave

Holding in my hand

A flower.

The flower is lotus. Although the poet is born in the world and grown in the world he is no longer soiled by the world.

Silence (1)

Silence (2)

Ts. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya (giữa) cùng các đồng nghiệp Ấn Độ

Tĩnh lặng (3) của Mai Văn Phấn

TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya chú giải

Phạm Minh Đăng dịch sang tiếng Việt

Tĩnh lặng

3.

Luồng sáng đang vây

Tôi

Dưới chân ngọn tháp

Ghé sát mặt bố tôi

(Người mất đã 3 năm)

Ghé sát bà nội tôi

(Người mất 27 năm về trước)

Bố tôi đã khỏi bệnh run tay

Bà nội không còn đi còng

Mỗi người dạy tôi cách nhớ

Một cách quên

Tôi trong suốt

Ra đi

Trong tay cầm một bông hoa.

Chú giải:

Trong phần trước, nhà thơ thiền định về dòng suối cuộc đời từ núi đổ bình lặng xuống hồ không gây tiếng động. Và khi nhà thơ nhìn vào mặt hồ trong suốt, một dòng ánh sáng phủ tràn nhà thơ. Dòng suối là dòng chảy. Và khi một dòng ánh sáng phủ tràn nhà thơ, đó là một hình ảnh cơ thể, mang cảm giác về sự chuyển động cơ thể. Nói khác đi, nhà thơ cảm thấy toàn bộ cơ thể của mình bao gồm cảm xúc và ý thức là một lối chuyển động. Cơ thể nhà thơ được chuyển hóa dưới chân tháp. Trước đó ta thấy một dòng suối trong khoảnh khắc chảy vào hồ trong suốt không một tiếng động. Hồ đó như thể phản chiếu lộ trình dòng suối hoặc dòng chảy cuộc đời là về chân ngọn tháp. Có thể chúng ta đi xuống từ ngọn núi đó và khi tiến dần về cái chết, chúng ta hiểu rằng chân ngọn tháp ngợp lời không thể diễn tả nổi và cuộc sống là một lời nguyện cầu không dứt. Khi chúng ta tiến đến đáy hồ, chúng ta thức tỉnh về ngọn tháp và ngay lúc đó, cuộc sống vốn dĩ tràn ngập nỗi buồn trở thành dòng ánh sáng chảy xuống từ cõi vô hạn bất khả hiểu và bất khả diễn giải, chỉ có thể cảm thức khi chúng ta nhìn vào cái chết. Và chúng ta bắt đầu cuộc sống nghi lễ khi ngồi dưới chân ngọn tháp.

Cuộc sống là một tháp thiêng hoặc một khám thờ dẫn ta về cõi không thể gọi tên. Điều này đưa tâm trí ta vào một thách thức ngược trở lại thời gian và không gian, cưỡng lại các định luật của nhiệt động lực học. Khi chúng ta ngược trở lại thời gian và không gian, chúng ta gặp lại cha, bà và mẹ. Họ dạy chúng ta cách quên. Nhà thơ Keats tìm cách quên lãng những cơn sốt và nỗi ưu phiền cuộc sống. Ban đầu ông nghĩ rượu có thể kéo ông khỏi nỗi bi thương của sinh tồn. Rồi sau ông cảm thấy mình có thể đồng hành loài chim sơn ca ẩn mình trong thế giới xanh lá, [tức loài chim] không bao giờ biết được những gì ta biết trong thế giới trần tục của mình. Bởi vậy ông dõi theo loài chim đó trên đôi cánh hút tầm mắt của thơ ca và mờ dần vào rừng xa mịt mùng lánh xa khối muộn phiền. Nhưng theo thời gian, ngôn từ chập chờn tuyệt vọng trong tâm trí ông và xóa tan những ảo tưởng của nhà thơ. Cả rượu lẫn ảo giác / huyễn tưởng không thể kéo chúng ta khỏi nỗi bi thương của sinh tồn. Con người cần nhìn nhận đời sống như một khối nhất thể từ điểm chết và nhận ra sự tái sinh có thể ở đó. Rập rờn sống động với một giao kèo sống tươi mới, con người có thể chống lại thời gian và các định luật nhiệt động lực học và họ được gặp tổ tiên của mình.

Những gì Mai Văn Phấn viết đều khởi nguồn từ kinh nghiệm. Cha ông mắc chứng Alzheimer và đã mất. Nhưng nhà thơ đã gặp cha mình lúc này khi ông có thể thấy cuộc sống vẫn bền bỉ vững vàng một khối. Ông thấy cha mình đã khỏi bệnh run tay. Cuộc gặp giữa nhà thơ với cha gợi nhớ tới cuộc gặp giữa Aeneas và cha trong thơ của Virgil. Trên thực tế, gặp gỡ người cha đã mất là chủ đề quen thuộc trong các hùng ca. Và đây cũng là một phần của hùng ca như nó đã / đang là. Nơi đây nhà thơ gặp cha mẹ và ông mình. Tâm trí và giác quan của chúng ta luôn bị kéo tới thế giới của ảo giác. Người anh hùng của nhà thơ Mai Văn Phấn buộc họ phải nhìn vào trong và do vậy chống lại ngọn thủy triều của thời gian thông qua thiền định.

Trong vũ trụ học Phật giáo, có 31 cõi. Trong đó có sáu cõi Dục Giới. Cõi người chỉ là một trong số đó. Cha mẹ chúng ta có thể đã rời cõi người. Nhưng rồi họ nương ở những cõi khác, có thể là Dục Giới. Và nhà thơ gặp lại tổ tiên của mình trong các cõi khác của Dục Giới. Và kìa! Cha đã khỏi bị cơn bệnh run tay hành hạ và bà nội không còn còng lưng nữa. Điều này có thể ư? Thuyết Duyên Khởi chỉ ra rằng những gì tồn hiện phụ thuộc vào vô số nguyên nhân và điều kiện nên tất cả những gì tồn hiện không có thật chất. Vì vậy việc nhìn thấy những người đã khuất, thấy cha và bà nội đã thoát khỏi bệnh tật thể chất nữa thức tỉnh nhà thơ rằng không có gì tồn hiện mà có thật chất. Họ cho nhà thơ biết cách họ đã quên các nỗi khổ trần thế. Một khi ta hiểu rằng thế giới nơi chúng ta đang chịu dày vò và những chịu đựng chúng ta trải nghiệm ở đây là không thật chất, một khi ta hiểu rằng đó chỉ là những ảo ảnh thuần tuý, ta có thể dứt bỏ. Nhận thức này khiến nhà thơ trong suốt bước ra khỏi tồn tại khổ đau. Ông vượt thoát cõi Dục Giới và thốt lên

Tôi trong suốt

Ra đi

Trong tay cầm một bông hoa.

Bông hoa ở đây là hoa sen. Mặc dù nhà thơ sinh ra và lớn lên trong thế giới này, nhưng ông đã không còn chịu sự ràng buộc của những bụi bặm thế gian.

Tĩnh lặng (1)

Tĩnh lặng (2)

Tranh của Họa sỹ Phạm Long Quận