Silence (20) - Tĩnh lặng (20). Mai Văn Phấn. Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya - chú giải. Traduction française Dominique de Miscault – Dịch sang tiếng Pháp. Takya Đỗ dịch sang tiếng Việt

Silence (20) by Mai Văn Phấn

Explicated by Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Translated into French by Dominique de Miscault

Translated into Vietnamese by Takya Đỗ

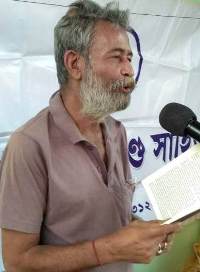

Ts. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Maivanphan.com:

Nhà thơ – TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya (Ấn Độ) vừa gửi tôi bài chú giải

đoạn 20 bài thơ liên khúc “Tĩnh lặng”, rút từ tập thơ “The Selected Poems of

Mai Văn Phấn” (Nxb. Hội Nhà văn, 2015) của tôi qua bản tiếng Anh của Nhà thơ Lê

Đình Nhất-Lang và Nhà thơ Susan Blanshard. Sau khi TS. Ramesh công bố bài chú

giải trên mạng Sefirah (Ấn Độ), Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Pháp Dominique de Miscault đã

dịch bài chú giải trên sang tiếng Pháp, Dịch giả Takya Đỗ đã dịch từ bản tiếng

Anh sang tiếng Việt. Xin được bầy tỏ lòng biết ơn sâu sắc nhất của tôi tới

Nhà thơ - TS. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya, Nhà thơ - Nghệ sỹ Dominique de

Miscault và Dịch giả Takya Đỗ đã dành thời gian và tâm huyết cho bài chú giải

này!

Poet - Doctor Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya (India) has just sent me an

explication on the 20th paragraph of the long poem

"Silence" selected from my poetry book “The Selected Poems of Mai Văn

Phấn” (Publishing House of The Vietnam Writer’s Association, 2015) through the

English version by Poet Nhat-Lang Le & Poet Susan Blanshard. Right after Dr. Ramesh

published the explication on Sefirah website (India), Poet - Artist Dominique

de Miscault translated the paragraph into French and Translator Takya Đỗ translated

from English version into Vietnamese. I

would like to express my deepest gratefulness for Poet - Dr. Ramesh Chandra

Mukhopadhyaya, Poet - Artist Dominique de Miscault and Translator Takya Đỗ for

having spent time and devotion on the translation for this brilliant

explication!

Silence

20.

A glass of water

Is placed in front of the

candle

Colorless light

Dropped from above

Shows the way for water to

settle

The more transparent I

become

Spike trap

Black arrows

Escape

From my soles and palms.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Nhat-Lang Le & Susan Blanshard)

Explication

On the surface the poem seems to put forward an absurd plot. There

is a glass of water in front of a candle. A colourless light descends on them

and shows the way how the waters could settle. And as soon as the water

settles, black arrows escape from the soles and the palms of the poet. The poet

becomes more transparent than ever.

When the water settles in the glass the poet becomes more

transparent than ever. This reads like a fairy tale for children. But tales for

children and the myths draw us to the deeper recesses of thoughts and feelings.

Roland Barthes observes that there could be readerly texts and writerly texts.

Writerly texts are those texts that make the readers think while the readerly

texts are those texts that need no help from the reader to get understood. But

the poetry of Mai Văn Phấn is always writerly text. It makes us think and feel

differently so that we are unknowingly drawn to the strange and heretofore

unknown deeps of meditation and contemplation. And what could be the glass of

water? Well the glass could be our body. Both are containers. And both the body

as well as the glass are brittle. What does the water in the glass stand for?

Is it not the mind in the body? Mind is as volatile and restless like water.

Mind has no colour of its own. The glass of water is placed in front of a

candle. The candle is the inward consciousness of a being. It is in the light

of inward consciousness that the poet is observing his mind and the body—the

glass of water. Once the mind introspects, a colourless light shows up. It drops from above. Could

light be colourless ever? Since light

travels as a wave all light has a frequency. Red is light with lowest frequency

that we can see. Violet is light with highest frequency that we can see. But

light havng higher frequency than violet and having lower frequency than red

could be deemed as colourless. The colourless light drops from above or from

the skies. No wonder it will create a shadow of the glass of water which could

be seen in the yellow lamplight. In other words the consciousness of the poet

can see his body and mind in the light of the Buddha nature. Buddha mind is

colourless because it reflects back all colours of our mundane existence. Its

light is something that is never on sea or land. So once this different kind of

light of the Buddha mind falls on the body and mind of the poet or the glass of

water it reflects back the gross and crudities inherent in any body and mind

whatever. They are like the spike traps that has man in the thrall of ignorance

or avidya. The light from above shows the water or the mind the way to settle.

The poets mind is therefore no longer restless and the poet reflecting back all

colours of the mundane world and existence becomes more transparent than ever.

Thus here is a poem that leaps forth from first hand experiences

of a yogi. It is truly a metaphysical poem that transcends the limits of

physics.

Explication par Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Traduction française Dominique de Miscault

Photo: Dominique de Miscault

Silence

20.

Un verre d'eau

devant une bougie

Une lumière

d’en haut

montre la voie à l'eau

Je suis transparent

Picots

flèches noires

s’échappent

de mes pieds et mes paumes.

Explication du Dr Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

À première vue, ce poème est absurde. Un

verre d'eau placé devant une bougie. Une lumière tombe du haut éclairant

l’apaisement de l’eau. Mais dès que l’eau est stabilisée, des flèches noires

s'échappent des pieds et des paumes du poète. Le poète devient plus transparent

que jamais.

Lorsque l'eau se stabilise dans le

verre, le poète devient plus transparent que jamais. Un vrai conte de fées à

raconter aux enfants. Mais les contes pour les enfants et les mythes nous

cachent des réalités profondes. Roland Barthes prétendait qu'il y a des textes

écrits et des textes à lire. Les textes écrits sont des textes qui obligent les

lecteurs à réfléchir alors que les textes à lire sont des textes qui sont

compris d’emblée. La poésie de Mai Van Phan est toujours un texte écrit. Mai

Van Phan nous fait réfléchir et ressentir différemment, ainsi sommes-nous

inconsciemment attirés dans d’étranges profondeurs jusqu'ici inconnues de notre

méditation ou contemplation. Mais que représente le verre d'eau ? Et si le

verre symbolisait notre corps. Un verre et un corps sont des contenants. Le

corps, les verres sont fragiles. Et que fait l’eau dans le verre ? N'est-ce pas

l'esprit dans le corps ? L'esprit est aussi volatile et agité que l'eau.

L’esprit est sans couleur. Le verre est placé devant une bougie. La bougie

représente la conscience intérieure. C'est à la lumière de la conscience

intérieure que le poète observe son esprit, le corps et le verre d'eau. Quand

l'esprit s’interroge, une lumière incolore apparaît. Elle tombe du haut. La

lumière peut-elle être incolore ? La lumière se déplace par ondes, toute

lumière a une fréquence. La fréquence du rouge est la plus basse, visible par

les yeux humains. Le violet a la fréquence la plus haute que nous puissions

voir. Ceci dit, une lumière ayant une fréquence plus élevée que la violette et

une fréquence inférieure à celle du rouge, pourrait être considérée, à nos

yeux, comme incolore. Une lumière incolore tombe d'en haut ou du ciel. Une

lampe jaune crée naturellement une ombre du verre. En d'autres termes, la

conscience du poète peut voir son corps et son esprit à la lumière du Bouddha.

L'esprit de Bouddha est incolore car il incarne toutes les couleurs de notre

existence. Sa lumière est inconnue sur la mer ou sur la terre. Donc, une fois que

cette lumière différente de l'esprit de Bouddha tombe sur le corps et l'esprit

du poète ou du verre d'eau, elle reflète les grossièretés et l’Avidyā[1]

inhérentes à tout corps et esprit. Nos corps sont comme des pièges qui

retiennent l'homme dans l’esclavage de l'ignorance ou de l'Avidyā. La lumière

tombante éclaire l'eau ou l'esprit et les guide pour les apaiser. L'esprit des

poètes n'est donc plus agité et le poète reflète toutes les couleurs du monde

et l'existence devient plus transparente que jamais.

Ainsi, voici un poème qui offre les

expériences d'un yogi expérimenté. C'est vraiment un poème métaphysique qui

transcende les limites de la physique.

__________

[1] Avidyā (sanskrit

IAST ; devanagari: अविद्या …). Dans

L’hindouisme, c'est d'abord l'ignorance de sa véritable nature recouverte par

les obscurcissements successifs de la conscience pure (le Soi) produits par le

désir et l'attachement. Dans le bouddhisme, avidyā est la première étape de la

chaîne des causes de la souffrance et l'un des Trois poisons.

Dominique de Miscault:

Artiste Plasticienne. De plages en pages qui se tournent. C’était hier, de 1967 à 1980, mais aussi avant hier, dominiquedemiscault.com. puis de 1981 à 1992. Et encore de 1992 à 2012 bien au delà des frontières. Aujourd’hui, la plage est blanche sous le bleu du soleil.

(http://www.dominiquedemiscault.fr)

Tĩnh lặng (20) của Mai Văn Phấn

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya chú giải

Takya Đỗ dịch sang tiếng Việt

Dịch giả Takya Đỗ

20.

Ly nước

Đặt trước ngọn nến

Ánh sáng không màu

Buông trên cao

Soi cho nước lắng xuống

Tôi dần trong lại

Bàn chông đen

Những mũi tên đen

Thoát ra

Từ gan bàn chân, bàn tay.

Chú giải:

Thoạt nhìn có vẻ như bài thơ đưa ra những tình tiết phi lý. Một ly nước

đặt trước một ngọn nến. Một làn ánh sáng không màu buông xuống những vật đó và

soi đường cho nước lắng xuống. Và ngay khi nước lắng xuống, những mũi tên đen

thoát ra khỏi gan bàn chân và bàn tay của nhà thơ. Nhà thơ trở nên trong suốt

hơn bao giờ hết.

Khi nước

lắng trong ly là lúc nhà thơ trở nên trong suốt hơn bao giờ. Nghe như truyện cổ

tích cho con trẻ vậy. Nhưng chuyện cổ tích cho con trẻ và chuyện thần thoại thu

hút chúng ta xuống những tầng tư duy và cảm giác sâu hơn. Roland Barthes(1) cho

rằng có thể có những văn bản khả độc và có những văn bản khả tác(2). Văn bản

khả tác là loại văn bản khiến độc giả phải suy ngẫm, trái lại văn bản khả độc

là loại văn bản không cần sự tương tác của độc giả để có thể hiểu được. Nhưng

thơ của Mai Văn Phấn luôn thuộc loại khả tác. Nó khiến chúng ta suy ngẫm và cảm

thụ rất khác đến đỗi chúng ta vô tình bị hút vào những tầng sâu tư duy và thiền

định. Và ly nước có thể là gì nhỉ? Ờ, ly nước có thể là thân thể chúng ta. Cả

hai đều là vật chứa. Và cả thân thể lẫn chiếc ly đều mỏng manh dễ vỡ. Thế nước

trong ly tượng trưng cho cái gì? Nó chẳng phải là tâm thức trong thân thể đó

sao? Tâm thức cũng phù động không yên chẳng khác gì nước. Bản thân tâm thức không

mang màu sắc. Ly nước kia được đặt trước một cây nến. Cây nến là tri

giác bên trong của sự sống. Chính dưới ánh sáng tri giác ấy nhà thơ

đang quan sát tâm thức của mình và cơ thể đó – ly nước. Một khi tâm thức tự xem

xét chính nó, ánh sáng không màu hiện ra. Nó từ trên buông xuống. Ánh sáng có

khi nào không màu không? Bởi ánh sáng di chuyển như sóng nên ánh sáng có tần

số. Màu đỏ là ánh sáng có tần số thấp nhất mà chúng ta thấy được. Màu tím là

ánh sáng có tần số cao nhất mà chúng ta thấy được. Nhưng ánh sáng có tần số cao

hơn màu tím và có tần số thấp hơn màu đỏ có thể được coi là không màu. Ánh sáng

không màu đó từ trên cao hay từ những tầng trời buông xuống. Lẽ dĩ nhiên nó sẽ

làm ly nước hắt bóng và có thể nhìn thấy trong ánh nến màu vàng. Nói cách khác,

tri giác của nhà thơ có thể nhìn thấy được thân thể và tâm thức của ông dưới

ánh sáng Phật tính tỏa chiếu. Phật tâm không màu sắc bởi nó phản

chiếu mọi màu sắc trong sự hiện hữu phàm trần của chúng ta. Ánh sáng Phật tâm

chẳng khi nào lại ở biển hay ở đất liền. Vì vậy một khi thứ ánh sáng Phật tâm

khác thường này tỏa chiếu xuống thân thể và tâm thức nhà thơ hay ly nước kia,

nó phản chiếu tính thô lậu và ô trọc cố hữu trong bất kỳ thân thể và tâm thức

nào. Những tính đó giống như những bàn chông kìm chặt con người vào sự u mê hay

vô minh [avidya]. Ánh sáng từ trên cao soi cho nước hay tâm thức một con

đường lắng xuống. Tâm thức của nhà thơ vì vậy mà không còn xáo trộn và nhà thơ

phản chiếu tất cả các màu sắc của cõi phàm và sự hiện tồn trở nên trong suốt hơn

bao giờ hết.

Thế nên đây là một bài thơ chợt nảy

từ trải nghiệm trực tiếp của một hành giả. Đây quả thực là một bài thơ siêu

hình vượt ra khỏi giới hạn vật lý.

___________

(1)

Roland Gérard Barthes (12/11/1915 – 26/3/1980):

nhà lý luận văn học, triết gia, nhà ngôn ngữ học, nhà phê bình và nhà kí hiệu

học của Pháp. (ND)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (1)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (2)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (3)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (4)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (5)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (6)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (7)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (8)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (9)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (10)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (11)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (12)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (13)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (14)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (15)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (16)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (17)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (18)

Tĩnh lặng - Silence (19)

Biography of Dr. Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Address: 6/ 1 Amrita Lal Nath lane P.0. Belur Math Dist Howrah West Bengal India Pin code711202. Date of Birth 11 02 1947. Education M.A [ triple] M Phil Ph D Sutrapitaka tirtha plus degree in homeopathy. He remains a retired teacher of B.B. College, Asansol, India. He has published books in different academic fields including religion, sociology, literature, economics, politics and so on. Most of his books have been written in vernacular i.e. Bengali. Was awarded gold medal by the University of Calcutta for studies in modern Bengali drama.

Tiểu sử Tiến sĩ Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

Địa chỉ: 6/ 1 đường Amrita Lal Nath hòm thư Belur Math Dist Howrah Tây Bengal Ấn Độ mã số 711202. Ngày sinh: 11 02 1947. Thạc sĩ văn chương, thạc sĩ triết học, tiến sĩ triết học [bộ ba] cùng với Bằng y học về phép chữa vi lượng đồng cân. Ông còn là một giảng viên đã nghỉ hưu của Trường đại học B.B, Asansol, Ấn Độ. Ông đã có những cuốn sách được xuất bản về nhiều lĩnh vực học thuật bao gồm tôn giáo, xã hội học, văn học, kinh tế, chính trị v.v. Hầu hết sách của ông đã được viết bằng tiếng bản địa là tiếng Bengal. Ông đã được tặng thưởng huy chương vàng của Trường đại học Calcutta về các nghiên cứu nghệ thuật sân khấu Bengal hiện đại.

Long Bien ou le pont de tous les songes - Dominique de Miscault